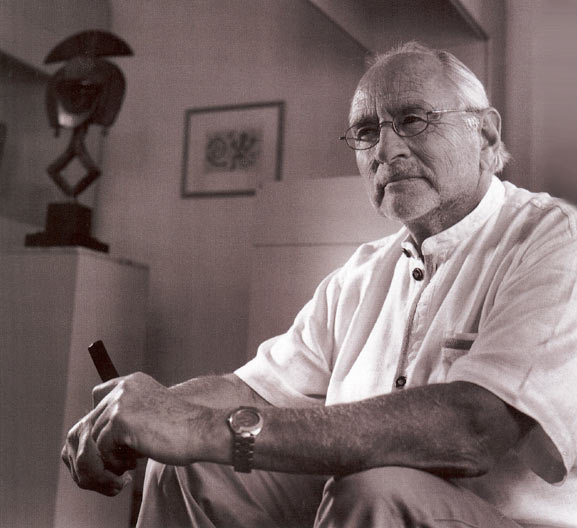

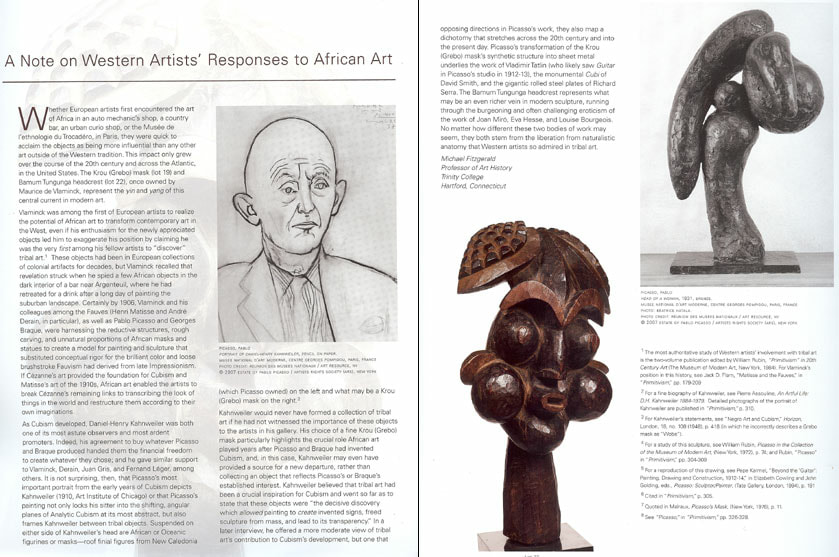

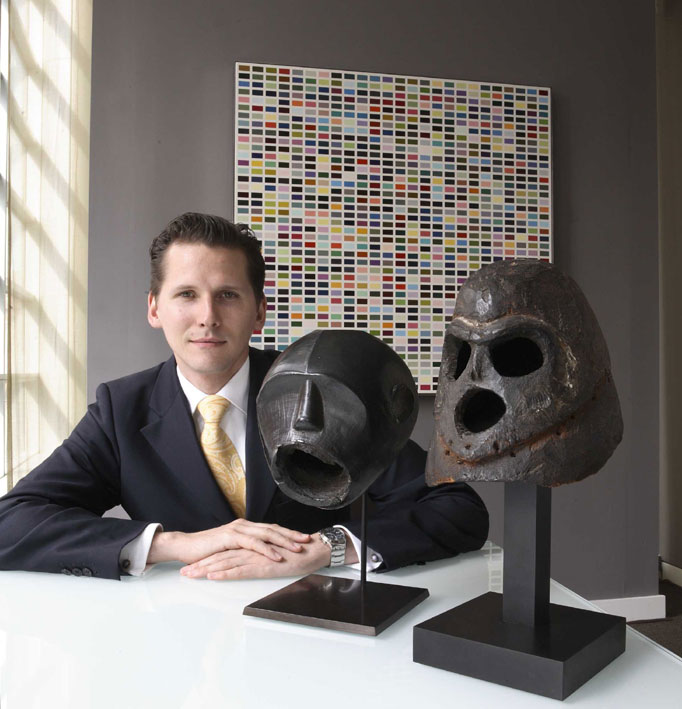

Heinrich Schweizer inside a private viewing room at Sotheby’s NY 2012

Heinrich Schweizer after coming to Sotheby’s in 2006 quickly made himself an indispensable and key figure at the number one auction company. A prodigy at an early age, through his deep curiosity and thirst for knowledge, is today one of the preeminent experts in African and Oceanic Art. He has studied individual workshops, physically handled more great objects and seen more private collections than most of us will in a lifetime. Sitting at the helm in New York as “Department Head”, he is uniquely qualified to bring us deep insights into every aspect of the marketplace like how it has changed, where it is going and how Sotheby’s serves its buyers and consignors. In this rare interview he lifts the veil of the corporate firm’s mystique, answering all questions thoroughly and honestly for our visitors. The core of this interview occurred “live” on the 5th floor of a private viewing room in May 2012 of the Sotheby’s offices in New York and was amended later.

Auliso: Can you tell me about your career path which led you to eventually becoming a specialist at Sotheby’s?

Heinrich Schweizer: My parents were both artists: my father a sculptor and my mother a painter and school teacher. My father, like many artists, had a collection of non-Western artworks that served as a source of inspiration. He collected Antiquities, Pre-Columbian, Indian and Southeast Asian, Japanese, and Chinese art, as well as owned a few works of African Art. As a child, for reasons unknown to me, I reacted to African art most strongly. Growing up in this kind of family, I also perceived that collecting was something natural to do. So I bought my first African sculpture when I was 10 years old, a small Ashanti gold weight I found in an antique store in my hometown of Munich. The owner of the store didn’t really know what it was and I was very proud because I could identify it. The price was 50 German Marks (the equivalent of about 25 dollars), which was much more than I had as a ten-year-old. I always enjoyed negotiating – the store owner was open to helping me – and eventually we agreed on payment terms that allowed me to make the acquisition. This little figure became the first piece in my collection and I still own it today. Much later I became interested in Oceanic art and bought my first piece in my early twenties. I always had a strong interest in art in general. Growing up, I especially appreciated modern art, first paintings by the artists of the Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider) and Bruecke (Bridge) groups, later on the Cubists. However, I never thought I would do anything professionally with my interests. My family was entirely artistic, everybody was a visual artist, performing artist or writer, and a great many collected art. In a way I was the black sheep of the family because I had more analytical interests. I had a couple of friends at school whose parents were lawyers, whom I greatly admired for their command of language and their structured and logical approach. So I wanted to study law and did so. After my graduation I went into legal academia and specialized in Foundation and Trust law and “Art Law” in a broader sense. It was with that background that I came to America.

Auliso: Early on, as a personal hobby, you were interviewing important people in our business?

Schweizer: Yes, I still do this for my own curiosity. I always greatly enjoyed meeting people and learning from them, especially those with much life experience. In turn, I have a preference for curious people. Curiosity and experience make for an interesting life. In terms of African and Oceanic art I had a catalyst moment when I was around 20. At the time there was a big annual art fair in Munich where one of the dealers exhibiting was the legendary Philippe Guimiot. I met him as a novice to the world of international art fairs and not knowing that much about that world, and asked him whether I could meet with him outside the context of the fair to ask him some questions on aesthetics and African Art. He was maybe a bit amused at this request by a very young man who obviously would not qualify as one of his customers, since I made it clear I didn’t have the funds to buy from him. He agreed to the meeting, which was supposed to be about 30 minutes, but one word led to the other and it lasted for five hours. We would be talking about aesthetics and quality, and I would say something pretty naive and uniformed. He would then go into a separate room in his hotel and pull out a few sculptures at a time, figures and masks, and explain not just every aspect of the actual works but also elucidate the cultural and stylistic relationships between them, and place the whole into the larger context of world art. His mind was operating on a much broader bandwidth than what I had ever encountered before in this field in Munich. At the end of our conversation there were 50 or 60 African sculptures laid out in his large hotel suite. The whole experience was quite shocking to me – shocking in the most positive sense of the word. I had just met a man who dedicated his entire life to art and questions of aesthetic appreciation, and I realized how much there was for me to learn. After this meeting I was determined to make African and Oceanic art an integral part of my life, a second pillar alongside my interest in law. Although subsequently I did not see Philippe for many years it goes without saying that I owe a lot to this man. He was as important to me as an inspiration as my parents. He gave me a magic moment that changed my life.

Philippe Guimiot

Auliso: What were the circumstances leading to your hiring as a specialist at Sotheby’s?

Schweizer: In a way this also had to do with my early meeting with Philippe Guimiot. I had bought a Nok terracotta head in the mid 1990’s when a lot of the Nigerian terracottas came onto the market. At the time you could buy very good quality for relatively little money. I studied the piece and developed a certain familiarity with this material but after a while found myself more drawn to wood sculpture. There I felt age and authenticity much harder to judge than in terracottas, and in fact I had been fooled a couple of times already. Being quite systematic in my approach to such issues I asked Philippe what advice he would give to a fledgling collector as to how best to learn about the age and authenticity of wood sculpture. His advice was simple: “Touch as many pieces as you possibly can, look at their collecting history and compare“. He said approximately: “You could go to a museum but you can’t handle the works in the way you need to in order to learn about them, or you can go to a commercial gallery, but the largest volume of objects you’ll see will be at an auction house.” He said: “You are so young that at some point you could interrupt your law studies for a few months and go to a big international auction house like Sotheby’s.” That made a lot of sense to me and we just left it there.

A couple of years later, when I was just about to finish my law degree, I remembered what Philippe had told me and contacted Sotheby’s and made a strong case that I wanted to come to New York to the African and Oceanic Art department. To get my visa, I had to justify my application with my legal background. So I started working as an unpaid intern one day a week in Sotheby’s legal department, where I worked on some quite interesting cultural property protection law cases. The rest of each week I was able to work in the African and Oceanic art department. This was in 2000 during the Egon Guenther single owner auction so there was much material for me to look at. I vividly remember the fantastic time I had. I was a fanatical worker. Every day I would come in before 9:00 am and often would stay until 9:00 or 10:00 pm. I would come in on weekends, too, and as often as I could I went to the local museums such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the American Museum of Natural History, and the Brooklyn Museum. I was taking everything in like a dry sponge.

After this apprenticeship was over, I went back to Germany, finished my law degree and then went on to academia. I enrolled in a PhD program in Art Law and came to realize that I had to finance this somehow. There was a distinguished newspaper in Germany called the “Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ)” which I subscribed to for many years. It is one of the few newspapers in Germany that has a dedicated section on the art market. One day I just called them up, curious whether they would ever run stories on the African Art market. I said to them that is something I would like to read. They said: “Well, is this an important field? It is a bit esoteric and we don’t really know much about it. Is this a relevant market?” I said: “Yes, there are big auctions in Paris and New York and top prices can be a million dollars.” They said: “That sounds interesting but we don’t have someone who can cover that, but it seems you know this field quite well, maybe you would want to try that?” They initially didn’t promise that what I wrote would be published. However, they liked my style and indeed published the very first article I submitted as a small column. This happened in the spring of 2001. A few weeks later I was in Paris to attend the sale of the Hubert Goldet collection of African, Oceanic and Pre-Columbian art. The newspaper didn’t ask me to go but I went anyway as it was a highly anticipated event and I just wanted to see it. It turned out to be this historic success of a two-day auction making some 88 million francs, at the time an unprecedented amount for a collection of this material. Reuters had it among the top ten news stories of the day and all the other newspapers got the Reuters news ticker. Not knowing this I shyly checked in with the newspaper and said I had just attended another African Art auction in Paris. They said: “Was this the Goldet auction that broke all those records?” I said yes, and they said: “You get a quarter page.” I wrote the article and it appeared on the front page of the art market section. From then I had my foot in the door with that newspaper. I published many articles thereafter and this, in turn, opened many doors and allowed me to meet lots of collectors. In the following years, if I wanted to visit a collector I just called them and explained my affiliation with the newspaper; people were generous and accepting of me.

I returned to America in 2004/2005 as a Visiting Researcher at Harvard Law School and a fellow of the German National Merit Foundation. Through the years since my Sotheby’s internship I stayed in touch with Jean Fritts who had been my mentor then. Jean, who is not only very knowledgeable in African and Oceanic art but also a great communicator with a fine sense for timing, informed me of a vacancy in the New York African and Oceanic art department just a few weeks before my term at Harvard was about to end. In a way, this shook me up as it was not part of my life plan and my feelings were mixed. On the one hand, my legal career was shaping up nicely and promised to be successful. On the other hand, very few people ever get an opportunity to do something that was their earliest childhood passion. Remember that I bought my first piece when I was ten years old. The question was whether I wanted to throw this secure legal field overboard to take a risk for my passion.

What made the difference in the end was a great interview process at Sotheby’s. I asked my interviewer, a Sotheby’s Vice-Chairman: “Why would you be interested in hiring someone like me who doesn’t really have any credentials in the art market?” While I knew a decent amount about African and Oceanic art I had not done anything in business. My interviewer was very blunt which I appreciated. She said: “We’ll know soon enough, when you jump into the water you’ll either sink or swim. If you swim you stay, if you sink you’ll go back to law!” I decided to take the chance. My first contract had a two week notice for both parties without cause. When I started the job I knew the first day that this experience could be very meaningful for my life. I quickly realized that there was a key part of my personality that I could never fully “live out” in academia: my competitive side. Today, competition is what I like best about my job.

Auliso: Did success seem to come easy for you at Sotheby’s?

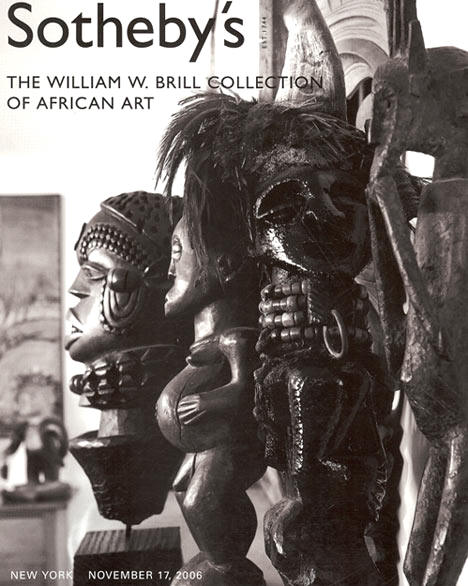

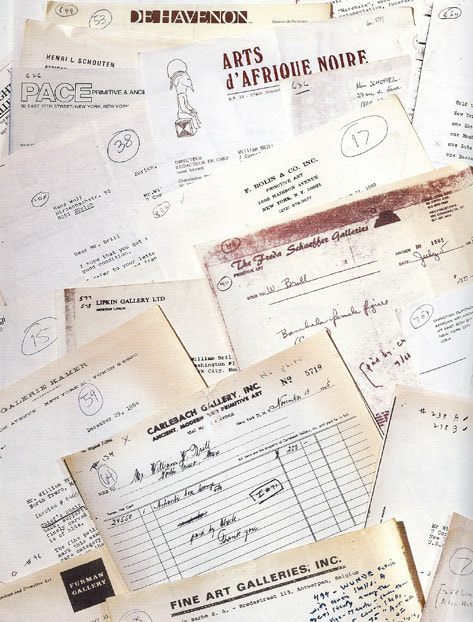

Schweizer: Since 2006, Sotheby’s African and Oceanic Art department in New York, the department for which I am responsible, has sold more than 150 million dollars of African and Oceanic art through auctions and private sales. We placed circa 100 million dollars through auction and about 50 million dollars through private sales. By contrast, in 2005, the year before I started, the department’s annual auction total was about 3.4 million dollars, and private sales were entirely negligible. In hindsight, if you have made the right decisions, it always looks easy. In my very first year I was presented with a great opportunity which some might call a lucky circumstance: the collection of the New Yorker William Brill about to come onto the market. This opportunity fell into my lap and I did not have much to do with winning this business. I basically entered the stage when the collection had already been consigned to Sotheby’s. Having been assembled primarily in the 1960s, the Brill collection was absolutely fresh to the market. The potential was obvious and I was extremely excited and motivated. However, seizing it was long and hard work.

As always with large projects, a great team of people supported me and helped put it all together. As this was nothing I had ever done before, however, everything took a huge amount of time. With 175 lots this was the largest collection of African art sold in New York since the Harry Franklin Collection in 1991. When working on the catalog, for about six weeks I got an average of 3 hours of sleep per night. There were a few nights when I napped for only 30 minutes on top of my office desk. I would keep working into the night and then had to meet clients the next morning in the same suit, shirt and tie I had been wearing the previous day. It was a very intense experience, but also an immensely rewarding one. I felt like that sponge again.

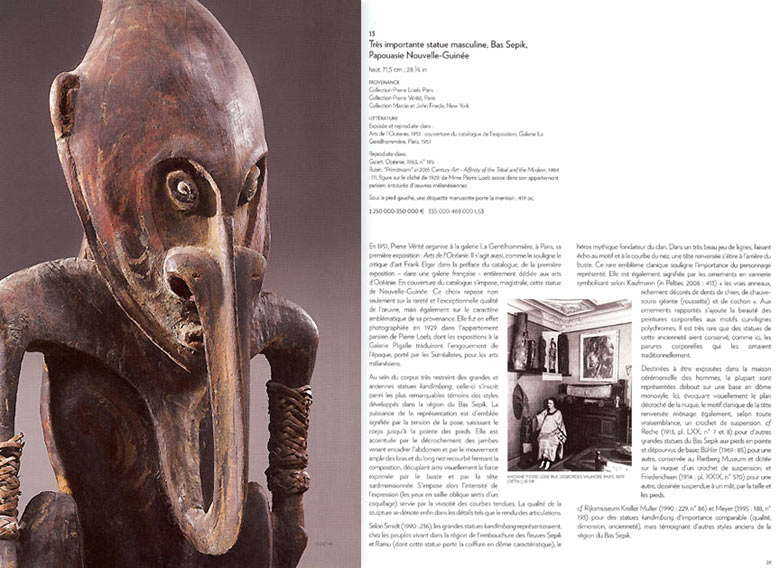

This was a time when the market was also ready for a jump in America. In June 2006, the Vérité auction in Paris had brought a number of new records; the sale of the Brill Collection followed suit in New York in November. The Vérité sale had been very successful. It was favored by a combination of factors, including a distinguished and specifically French provenance, the newly opened French auction market with Paris at its center, the opening of the Quai Branly Museum the same week as the sale, and very strong French media interest surrounding these events. Many people thought that the Vérité auction would mark the all-time-high in the market for many years to come and that such a success would only be possible in Paris with its rich tradition of collecting in these fields. New York was perceived as a market in decline which would never be able to resurrect to its past glory as the most important auction venue in the world. Little did they know.

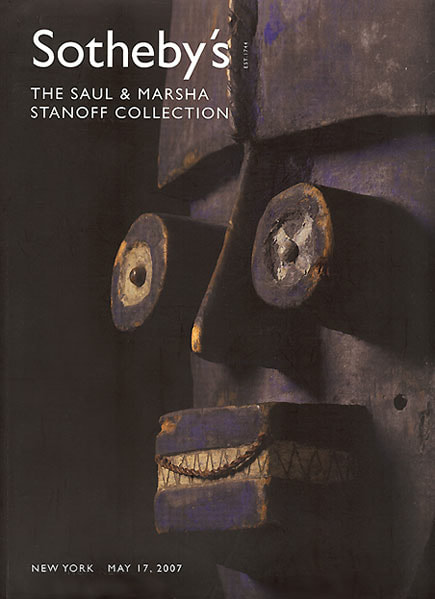

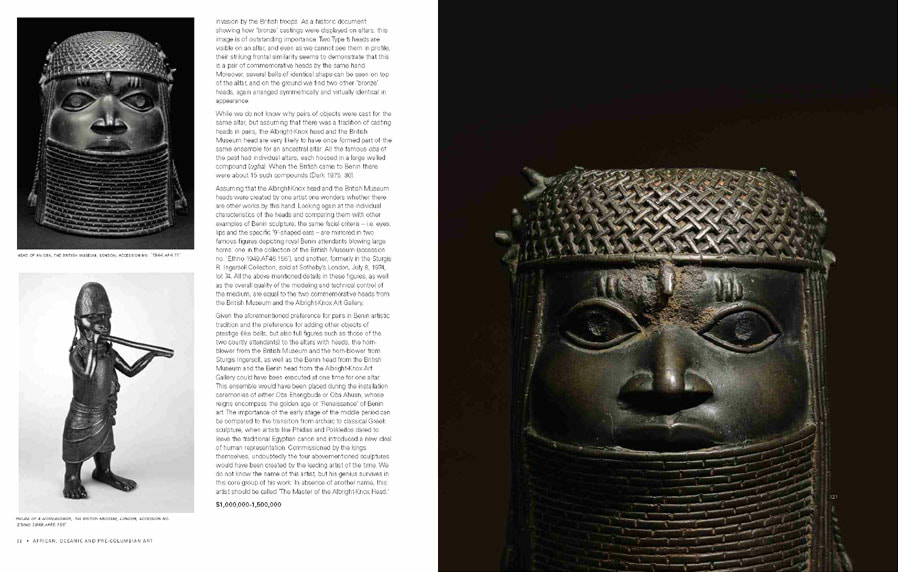

The Brill auction turned out to be hugely successful, with every single lot sold and the total result two times the presale high-estimate. The following spring, we presented the Saul and Marcia Stanoff Collection together with a few masterpieces deaccessioned by the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo. This auction broke all records and generated $25 million – half the sum that the Vérité sale had totaled but with only one quarter of lots. That sale of May 2007 was the true turning point in the market, marking the beginning of a new era. The quality of the works on offer was so great that it attracted the interest of art collectors outside the African and Oceanic art field, who, for the first time, entered the market on a broad front. Our cultivation and continuous expansion of this collector group led to the reassessment of the top of the market in our category that we have been witnessing in the last five years up through today.

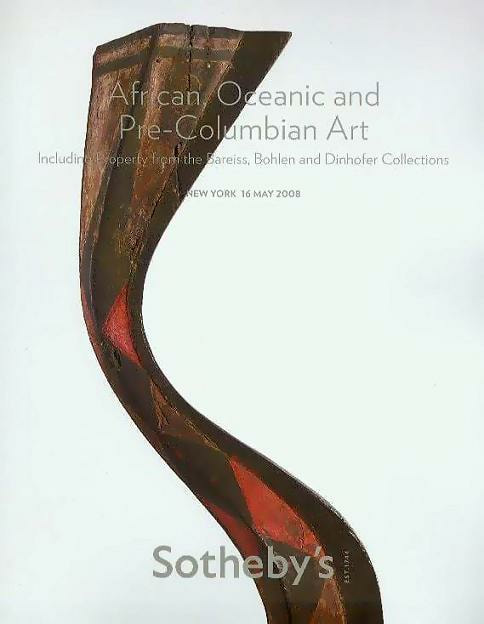

This trend became still more evident the following year, 2008, when we were entrusted with the sale of an iconic masterpiece of African art, the Dinhofer Baga Serpent. For many people it was never conceivable that a Baga serpent figure, so abstract, could ever go for an important price. This sculpture, however, was distinguished from many other African artworks by what I would call its universal appeal, which opened it up to the new group of buyers that had made its first appearance in the market the previous year in the Stanoff auction. When it sold for 3.3 million dollars (New York, May 16, 2008, lot 58) it became the fifth most expensive work of African art of all time and today it still ranks among the top ten. Here was confirmation that the auction market was moving into a very different direction from before. Today we know that it was heading to a New World.

Auliso: I noticed changes in the Sotheby’s catalogs right around when you were hired.

Schweizer: I believe that whenever one comes into a new position, one oughtn’t to carry baggage from the past. This allows one to try new things. All the changes we implemented were not radical but rather small. However, many small tools together still added up to really changing the way we presented African and Oceanic art. I’ll mention a few things. First, there was the terminology. I always looked at African and Oceanic art from a universal perspective, which was how my parents brought me up. I never “compartmentalized” between different categories of art or bought into how you must use different lingo when talking about Western art versus Indian art, say, or Antiquities or African and Oceanic art… What amazed me when I entered this field was that most people were still calling it “tribal art”. Galleries and auction houses, big and small, even certain museum curators used that term. I mean, what does it really say? The emphasis is placed not on art but a somewhat vague concept of “tribalism” and “tribal culture”. It evokes certain preconceived associations, almost like “sweet and sour sauce” on the menu of a Chinese restaurant. There is no doubt that the term “tribal” is a historically contingent or quasi-imperialist remnant of the colonial era. It is the result of a Western imperial perspective with condescending overtones and reveals a unilateral view on civilizational progress. We don’t talk about the “Irish tribe” or the “English tribe” so why would we use this terminology when talking about African or Oceanic people? The more antiquated term “Primitive Art” is by no means better. What these terms basically suggest is that the most important common denominator of these artworks is their origin in tribal societies. This logic is obviously very arbitrary and of little help if one compares the small surreal artworks created by the Lega, an isolated people of hunters and gatherers living in the eastern Congo, to the majestic Benin metal casts, an art form centered in the dynastic traditions of the ruling family of an empire that for several centuries was the dominant military force in Western Africa, and had trade relationships with the Portuguese since the 15th century. To both examples, in my mind, it is problematic to apply terms such as “tribal” or “primitive”; rather, the very use appears as holdover from the colonial era.

By contrast, I have always thought more in terms of the “individual artist”. And if we have categories such as French Art, English Art, Chinese Art, Japanese Art, Indian Art, why wouldn’t one at least talk about African Art and Oceanic Art? So it was important to me, first off, to apply the same art historical principles that were established in other disciplines also to African and Oceanic art. We thus adopted this terminology consistently, and introduced art historical standards into our catalog presentations. A direct consequence of this approach and one of my strong personal interests is the identification of individual artists, their workshops and regional styles in African Art. I am sure you have also noted this in our sale catalogs.

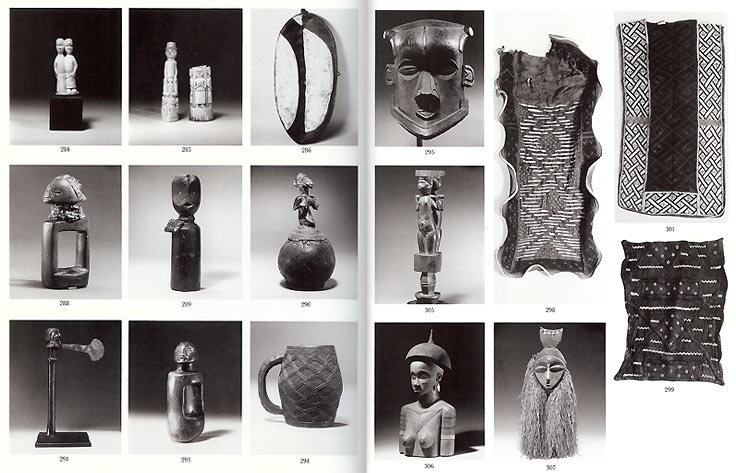

Another change we introduced was the visual way we presented African art inside our catalogs. For decades, auction catalogs as well as most scholarly and other publications photographed African and Oceanic sculpture on black backgrounds. Why? In talking to many photographers, I was always told that sculpture benefits from dramatic lighting, as opposed to painting where you want the lighting to be very flat and even. Because of the shadows on the background that dramatic lighting can produce, it was common sense to use a dark background. There is also a technical challenge if one photographs on a light background: the reflecting light from the background can lead to a loss of definition of the sculpture’s outline. This was a technical issue, not quite easy to figure out but turned out to be solvable.

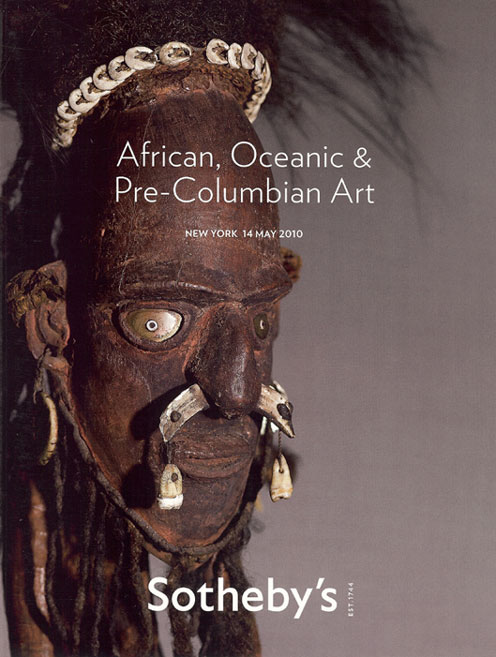

So for my entire first year, working with Sotheby’s photographers, we experimented a lot with different backgrounds. In the end we found a way to shoot sculptures on white backgrounds without losing either definition or dramatic effect, and we have perfected our technique continuously in that regard. We launched this new look for the first time in 2007 starting with the Stanoff sale. It was quite interesting to hear the reactions. The traditional collectors of African Art all said “hmm, this looks strange but not bad.” But when I talked to other colleagues at Sotheby’s across other departments, they all said this looks really sexy. Most importantly, the fine art collectors who entered the market in 2007 responded positively. We used this look again in 2008, 2009, and 2010. And then all of a sudden other auction houses started doing it, first Christies and then Bonham’s. Then you saw galleries using this look in their ads. Then new scholarly publications also adopted this look. Now it seems everybody is shooting on white, and it is of course gratifying to know we had come up with this idea. It seems like such a minor thing but when you think of it: now, as you open a book or catalog for Old Master Paintings, Greek and Roman sculpture, Contemporary Art and African Art — it all has the same look and you don’t have the feeling anymore that you are walking into the “dark-forest-of-tribalism”. And if you are a collector new to this field, you want to be able to relate to it and not be repelled by a look you are not familiar with.

|  |

Auliso: What are the most challenging and gratifying aspects of your job?

Schweizer: The most challenging is to maintain a consistently high level of quality in whatever you do. Most important in our profession is to protect our clients, be it the buyer or the seller. In the art market there are large amounts of money involved. First, you always have to be aware of the risks for a “buyer”. The worst that can happen is that an artwork one sold turns out not to be authentic or is discovered to be heavily restored or is for some other reason not worth the money that the buyer invested. At the same time, one has to protect the “seller”, which means avoiding selling his property below its market value, for example because one hasn’t researched it sufficiently and doesn’t recognize its rarity and value. So there is a lot of responsibility on those two fronts, protecting clients on both sides. The most gratifying experience is when it all works, making the seller and buyer happy and delivering a high-quality service and product.

Auliso: Do you see any broad trends emerging in the market?

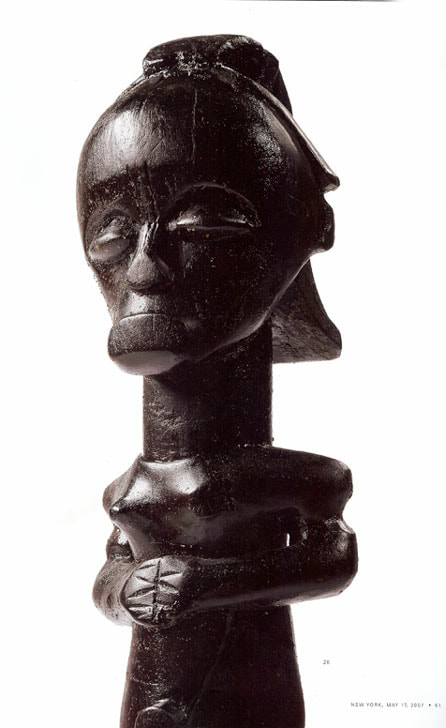

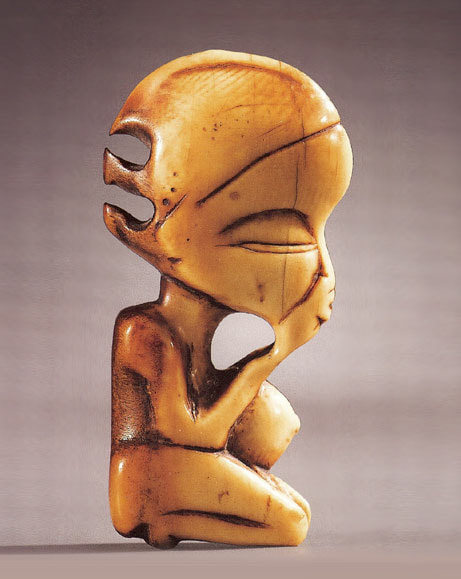

Schweizer: I think that the art market in general in the 21st century is becoming less compartmentalized by regions or categories of artworks. There is one category that everybody wants: the universal masterpiece, the artwork that defies categorization and transcends regional styles and eras. Once you are discussing such an artwork, it doesn’t matter whether the work is African or Oceanic, 500 years old or 50 years old. We’ve seen a number of such works in the past two years going for very strong prices at auction. One great example would be our Hungana Ivory Pendant which we sold in Paris last year (December 14, 2011, lot 64). It had an estimate of 30-50,000 Euros and was sought-after by a dozen of bidders, eventually selling for over one million dollars to a client who was bidding with me on the phone. It didn’t sell for that much because it was an “ivory” or a “miniature”, or an “amulet” or “Congolese”. Of course it could be categorized in all those terms, but it was much more than that. In the end it sold for an outstanding price because the artist had created a sculpture that carried so much dignity and spirituality that it became accessible to a very broad audience reaching far beyond the limits of the traditional African Art market.

Auliso: Is there a specific piece you’re especially proud of playing a key role in bringing to market?

Schweizer: The first especially important work to me on a personal level was the Dinhofer Baga Serpent (May 16, 2008, lot 58). At the time we put it up for sale, it was given the highest estimate ever placed on an African sculpture, 1.5-2 million dollars. I think before the Dinhofer Baga Serpent only the Fang “ngil” mask in the Vérité sale ever had a similar estimate, after converting its price of 1-1.5 million euros into dollars (1.25-1.75 million dollars). But there, you’re talking about Fang, one of the most iconic genres of African Art – and it was not only just a Fang mask but a mask of the most iconic type (ngil) and arguably the best in the world. For the Dinhofer Baga Serpent it was a much bolder move to go out there and say “this is a Baga sculpture from Guinea Bissau” – traditionally not one of the most popular and sought-after genres in African art – place it on the cover of the catalog and appraise it higher than any work of African sculpture at auction had ever been appraised. The highest price a similar sculpture had ever sold for was a fraction of our estimate. On the other hand, there was no work of comparable quality on the market in probably the last 40 years. In absolute terms it was one of the best two or three in the world, and this count includes the Lazard Serpent at the Louvre which will never be for sale.

I was talking before about “responsibility”. This was the most important artwork in the collection of Shelly and Norman Dinhofer, two very passionate collectors who never had a lot of money in their life, but shared a great eye. They had been living with this masterpiece in a modest house in Brooklyn since 1967, having bought it then from Pierre Matisse in New York for $3,600. The Dinhofers had three children who grew up together with that sculpture. There was this kind of “family myth” that the serpent was watching out for them. They believed that as long as the serpent was in the family, it offered protection and nothing could ever happen to them. You meet people like this and have a chance to get to know them, and over time you become friends. You talk to their children. It was apparent how important this object was to them, and they never really wanted to sell. Then, at one point in time they were in their 80s, their house with an old-fashioned staircase was becoming uncomfortable to move around in, and they were looking at how they could possibly move to a smaller space in Manhattan. They needed a certain amount of money to do that and knew they wouldn’t have all that much space anymore, and this is why they heavy-heartedly decided to sell their collection. So one day you find yourself in a position where you are entrusted with this magnificent work, and of course you want to do justice to this object, which I believe to be one of the great monumental sculptures of African Art. Then, however, there is the personal component. Back to “responsibility”: you meet these wonderfully passionate people, you start to care about them, they become your friends and you know that their life plan depends on the success of the sale. It is not just them, either, but also three children and a couple of grandchildren, all of whom look to you with their hopes and expectations. And everything is public – the presentation in the catalog, the auction, and every step you take can be seen. You must be made for the auction business, for what you sometimes need are very strong nerves. As everybody knows, though, it all worked out well in the end.

What is fascinating about the Dinhofer Baga Serpent sale is that on the other side my story with the buyer was very special, too. I was bidding on the phone with this collector who, while an ambitious man with a great eye, had never spent this amount of money for a work of African sculpture. Before the auction he said to me: “you know what, this figure is for a museum, it’s too important for me… How could I justify owning something like this?” We had a lot of discussion before the auction and he finally said to me “if it goes within the estimate, I’m ready to buy it, but if it goes above that I’m out.” So, we were bidding together and went in at 1.4 million and bid it up at 2 million – when he dropped out. Two other collectors went on battling and it shot up to 2.5, 2.6, 2.7, and on to 2.8 million and then stopped. With the auctioneer waiting a little I said to him: “Now you get a second chance. Do you want to own this work?” He said “I don’t know… what do you think?” I said: “The only thing I know is if you buy this work and live with it, it will take you, as a collector and as a person, to a whole new level in your life. Living with such a masterpiece means you’ll never look at art the same way you did before.” He said: “OKAY, I’m in”, the auctioneer said “Welcome back!” and we managed to place the winning bid at 3.3 million dollars. The room lit up with applause and I believe that everybody realized there was an inner struggle going on in this collector who corrected his previous decision and decided to fight to the end for his passion. In this very moment a great collector was born and what I had said to him in the storm of the situation proved absolutely true. This purchase changed his life, and what he has bought afterwards does not compare to what he bought before. He has bought only great works afterwards and if he continues this way and stays disciplined he is sure to build one of the greatest collections in the world, with the Baga Serpent as the centerpiece. So, from the seller to the buyer – it was a truly rewarding experience.

Auliso: It is apparent that more and more collections are going straight to auction and bypassing dealers that helped build these collections. From a dealer perspective this is a negative. What are your views?

Schweizer: I don’t want to judge it in “positive” or “negative” terms but rather accept it as a fact. The reality today is that the auction houses are sourcing the vast majority of top quality works coming to market. Sotheby’s holds an 80 percent market share over Christie’s worldwide. In New York our lead is even bigger and exceeds 90 percent. The question is why and the answer has to do with globalization. Think back to a time when every city had a large number of independent convenience stores. A smaller convenience store might cater to one neighborhood, a large one to a quarter or at best to a small city. What these stores had in common was that they sold mainly local products to a local audience. While the offer might have comprised high quality in certain categories, the selection was by nature limited, and often low quality could also be sold in the absence of competition between vendors, especially in more remote areas. As economies and individual markets became increasingly global, some stores increased their reach and started selling not only European but also Asian, Australian or South American products. Especially those consumers interested in top quality as well as diversity benefited from this development as they could buy anything they wanted at any time, as long as they paid the price. Of course, the bigger and more international a business, the easier it was to source a diversified selection of products and place them with an international audience. Sooner or later a few companies gained “critical mass” and became market leaders.

I think this is what happened between the “traditional market” of African and Oceanic Art, which was first dominated by dealers and galleries, and today’s “auction market.” What you could find in the old-style galleries on the Grand Sablon in Brussels or the Quartier Saint Germain in Paris was usually the material dealers found locally. Of course it was great for buyers to go there because sometimes you could find something of masterpiece-quality in a style underappreciated in the local market. But that was not good for the seller. Today, in contrast, a business like Sotheby’s with nearly 100 offices worldwide, and regional representatives in all the world’s major cities, has a network of potential sellers and buyers that (a) cannot be matched by a regular-sized gallery and (b) ensures that both buyer and seller are getting a fair deal. The key question for us is getting the right product. As long as we are able to find artworks which are of appeal to an international audience, we can place these very well with our clients. The better our track record, the more incentive collectors have to sell through us, and the better the next auction will be. It is therefore in our vital interest to understand in which quality segment our international clientele has the strongest interest. The current market shows a clear, strong interest in top quality artworks from canonic African styles, especially those that are well-documented by virtue of their inclusion in important publications and exhibitions. If you go back 30 years, auctions were much larger, often comprising between 300 and 400 works of mixed quality. Back then, knowledgeable dealers would sometimes come to the auction to advise their clients, but mostly to pick out the best works for themselves. Today the auction houses are selling directly to the world’s most important collectors. It is a big change.

PART 2

Auliso: Some of my dealer colleagues have the perception that Sotheby’s is consciously taking away their clients, thus hurting their business. Your thoughts on that notion?

Schweizer: I strongly disagree with this idea because it is not well-informed. The truth is that the international auction houses are persistently producing new collectors. We are introducing people to African and Oceanic Art who could never have imagined they would be attracted to this field. I would say that 50 percent of our clients have been in the market for 10 years or more, and 50 percent have joined the market more recently. Many of the newer collectors have developed a great passion for this field. Newer collectors often start out at auction because they appreciate the level of expertise, compliance standards and transparency of pricing. But with time they gain confidence in their own judgment, start going to fairs and venture into the gallery world where they also start buying. In the end, these new collectors strengthen the market and everyone benefits.

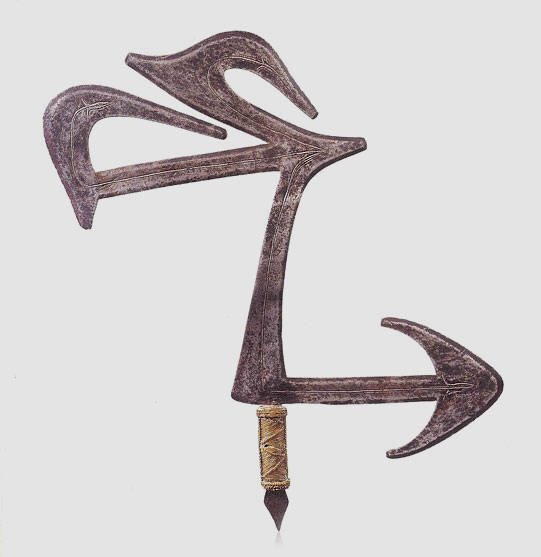

Auliso: In your December 2011 sale in Paris a Cameroon throwing knife sold for 216,000 euros and a Songye axe sold for an astonishing 384,750 euros. I’ve sold African weapons for years, but if I asked a similar price I would be called “insane”! Why do you think these sold for so much?

Schweizer: Well, a group of knives was consigned to us that all came from the same collection, of a collector who for many years specialized in collecting African weapons. A set of characteristics distinguished these weapons from 99 percent of the other weapons you see on the market. The blacksmithing was very good, the forms were exceptionally elegant, some showed a refined copper inlay, the Leo Frobenius provenance was excellent, and so on. There is an argument to be made then, that these weapons to begin with were distinguished from the vast majority of other weapons on the market. Now, what has changed in the 2011-12 market is that buyers today know that while African Art has been for decades a “niche market”, it is now considered “fine art” and a collecting field of universal appeal. Whenever a market “shifts” like this from one side to another you have a reassessment taking place in all its categories. The prices we are seeing today have no precedents. Simply put, what we are witnessing is that certain artworks are migrating from one market into another – from the local into the global market. So with the weapons you mention, several collectors determined for themselves what the value was and two of them were prepared to tread into frontier territory. Five or ten years ago, I would say, the average African weapon was selling for between $500-$1,500, and if you had an outstanding example, maybe a dealer could sell it for $8,000, and at auction, maybe in the heat of the moment it could go up to $15,000? However, today $15,000 is not a lot of money anymore for many people – also a result of globalization and the creation of new wealth that came with it. Today people are seeking out their own thresholds. In this situation there were two collectors who said: “To me this is really worth that much”. The counter-bidder thinks: “Well, at this level I’ll still be unhappy if someone else gets it”, so they put in another bid. And so it goes.

Auliso: Talk more about these new sophisticated collectors that you say are not “compartmentalizing” their buying. Are these collectors attending the fairs?

Schweizer: Yes, today when there is a great work of art on the market it does not matter whether it was created by a 16th century Dutch Master, a 20th century European Master, or a 19th century African master carver. The collections being built today are very eclectic, combing different regions and eras. For a collector of so many different areas, it simply becomes a logistical problem to go to every regional art fair. Instead, the annual spring and fall sales of Modern and Contemporary art conducted by major auction houses in New York, bringing together say a hundred African sculptures, fifty modern sculptures and five hundred paintings are a much more convenient hunting ground. Once you are at Sotheby’s and know the experts in the collecting fields of your interest, you can at the same time preview Modern Art, Contemporary Art, Old Master Paintings, Antiquities, as well as African and Oceanic art. Today’s collectors often collect in several or all of these different categories, and more. Of course many of these eclectic collectors also go to Maastricht in March, Art Basel in June, and every other year also to the Biennale (des Antiquaires) in Paris in September. And the more edgy crowd also goes to Art Basel Miami. However, that’s really only in addition to the May and November auctions in New York which also serve as an important measure of the pulse of the market. Sotheby’s African and Oceanic Art auctions are strategically scheduled around these major auctions and we greatly benefit from the exposure to the international community of high end art collectors. A collector who attends these main events, all in different locations, already has a very busy schedule. Going then to still more African and Oceanic Art fairs in Brussels, San Francisco, Paris and New York easily becomes too much.

Auliso: It seems to me that the market for African and Oceanic art has become bifurcated between auctions and galleries. How do you describe these two distinct markets?

Schweizer: The traditional gallery market for African Art has – on average – not changed very much over the last 10-20 years. It is basically the same collectors, the same dealers and the same fair schedule. Prices have been relatively stable in that market. For most objects there may not have been much appreciation in the last 10 years but you probably didn’t lose any money either. The other market is what I call “The African and Oceanic Fine Art Market”. Here we are talking about collectors with a universal perspective on art. The number of such collectors has always been much smaller than the number of collectors of just African and Oceanic objects which can be of either artistic or ethnographic merit. A lot of material that might excite a traditional specialized collector of African Art does not have the same effect on these collectors to whom African and Oceanic Art is only one of several collecting interests. The latter spend a lot of time looking at and thinking about art in general. They often have extremely refined tastes, shaped by different art fields and eras. And they know exactly what they want. There are certain African and Oceanic artworks that qualify for this category of collector, and it is our skill at Sotheby’s to be able to identify these works and lead them from the traditional market, where they are found with old-time collectors, to the “new market” we have developed, to be purchased by the new generation of art collectors. Between these two markets there is a big gap in prices.

As an example: I’m German and there were two separate German states up until 1990 when the East and West were united. Today Berlin is a single large city and the capital of Germany, but for 45 years East and West Berlin were separated by The Wall and the German capital was Bonn. Real estate in the Western part of Berlin was more expensive than in the Eastern part. In the East you could buy, say, an entire apartment building in Prenzlauer Berg (East Berlin neighborhood) for the price of an individual apartment in the West. When The Wall came down, the prices of East Berlin real estate quickly rose to the level of West Berlin. But it didn’t stop there; soon enough people were willing to double, triple the previous West Berlin value. Now, if you were living in East Berlin for the last 40 years and accustomed to your local market, you might have said: “Prices are crazy…” However, what people couldn’t see was that the fall of The Wall had initiated an irrevocable process at the end of which stood not only the collapse of the East German state but of the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc as a whole, and the end of the Cold War. In the following years Berlin was to be transformed from an isolated city into its opposite – an international hub and the capital of a large European country. Its vibrant artist community attracts Hollywood stars who buy second homes, lawyers from New York, businessmen from China and Russia, et al. From today’s viewpoint, whether the prices paid in 1990 were double or triple the level of 1989, these prices were still far from the reality of a global market. So in 1990, prices that looked “crazy” were really just the beginning of a broad expansion of the market. When buyers enter a market which for one reason or another was “secluded”, the rise of prices is a natural consequence.

When I just think of the term “African and Oceanic Art” versus “Tribal Art” – and I hope you don’t take any personal offense to this since your website and business are called Tribalmania – it reminds me a lot of the Berlin Wall. To me the term “tribal” is like a remnant from another time, a Cold War against the aesthetics of African and Oceanic cultures. The term “tribal” has done a great disservice to the integration of African and Oceanic Art into the canon of world art as it emphasizes the source cultures – we are talking about cultures covering more than two thirds of the world – as “the other”, with instant associations to the “uncivilized” and the “savage”. I am especially surprised that many members of the trade in what I described earlier as the “traditional market” still use the term “tribal”, as it has for a long time dramatically limited the growth potential of the African and Oceanic Art market. If you don’t define a gemstone as such you will never be able to sell it for the price of a gemstone. You will always just be able to sell it for the price of a stone. I always believed that calling works by African and Oceanic masters “African and Oceanic Art” does them much more justice. Sotheby’s was the first to apply this philosophy to our auctions, way ahead of anybody else in the field. Up until a few years ago even Christie’s still had a “Tribal Art” department. As a consequence, the two auction companies have very different client bases. The massive participation of seasoned fine art collectors in our sales is consistently producing new records at Sotheby’s. A fine art collector spending 20 million dollars for a European Master has usually no problem placing a 200,000 dollar bid in an African and Oceanic art sale even if this means 100,000 dollars more than a previous record. If you as a seller want to capitalize on the difference between the traditional market and the new market, you are best advised to use Sotheby’s as a “bridge” where your property can walk from one side to the other.

Auliso: How important is provenance nowadays?

Schweizer: Before answering this question I want to clarify that provenance is not limited to ownership, but also includes the publication and exhibition history of an artwork. Corresponding to the evolution of the African and Oceanic Art market over the last decades, from an antiques market into a sophisticated fine arts market, the importance of provenance has increased significantly.

First of all it is important to understand the perspective of the buyer. Anybody who spends a significant amount of money for whatever category of property, e.g., real estate, wants to know that some basic criteria are fulfilled on the seller’s side, including that the seller has good title and is able to transfer this title free of any third-party claims. For tangible property this also includes legal export and import from and to all the countries where an object was situated. Special laws apply to archaeological objects, works made from sensitive materials such as elephant ivory. Buyers want to feel assured that their financial and emotional investment in an artwork is protected against “loss and damage”, and before making a commitment they want to know there won’t be a bad surprise later on.

Provenance information offers quintessential information in that regard and every seller and his or her agent, i.e. auction houses, galleries and private dealers, should do the maximum to make the purchaser feel comfortable and share all information available. In earlier times the financial commitments weren’t as significant, therefore buyers and sellers adopted a much more casual attitude when it came to questions of provenance. Today, however, you spend the equivalent of the price of a fancy car, an apartment or a house, and this is naturally reflected in the due diligence process. In a world that is getting more connected every day, with collectors living in multiple locations over the course of their life, art moves frequently across borders, and this also means from one country’s legislation into another. The traditional “from an old Belgian collection” that satisfied collectors thirty years ago doesn’t do it anymore. Buyers today expect detailed information, including the names of previous owners and their countries of residence.

Second, diligent research of the publication and exhibition history can also help to identify or exclude condition issues of an artwork, later alterations, etc. For example, a New Guinea Mundugumor wusear figure, aka a “flute stopper”, that was documented in the 1920s with a shiny surface and without any feather and shell ornaments, and today is offered with a crusty patina and a headband made of cassowary feathers, has clearly been altered during its lifetime and this alteration is reflected in the value – and should be reflected in a lower price! On the other hand, if an object has been photographed in situ before it was collected from its African or Oceanic home, and is still in its original condition today, that adds to the value. So in its second manifestation, provenance information influences value.

Third, there are certain collectors who are well-known for their connoisseurship and excellent taste, who have been important field collectors, or who are otherwise famous. We can think of explorers such as Captain James Cook or early visitors like the medical doctor Emile Torday. Or of early collectors such as Arthur Speyer or Georges de Miré. Or of the celebrities and taste-makers like Helena Rubinstein or William McCarty-Cooper. More recently, the inclusion of a work in specific museum exhibitions such as William Rubin’s 1984 show “’Primitivism’ in 20th Century Art” has also created its own category of provenance. Such provenance adds a certain cachet to an artwork that might be of special appeal to a collector. However, it really depends on personal interest: some collectors are more interested in history and science, others more in lifestyle. The first group might care more about Captain Cook, the second group more about Helena Rubinstein. It is our job to know exactly which collector has which kind of interest, and then to match the two.

For most collectors, provenance is just one of many factors to consider when making an acquisition. In most cases it does not affect the value of an artwork; what it does is to make the buyer feel “comfortable” with his or her financial commitment. On rare occasions, however, an artwork of exceptional quality is accompanied by very prestigious provenance of the aforementioned third category. Such a combination results in a certain “magic”. We have seen in our most recent auctions what this magic can do.

Given these considerations, Sotheby’s is very focused on provenance research. Between Alex Grogan and myself in New York, Jean Fritts and Paul Lewis in London, and Marguerite de Sabran, Patrick Caput and Alexis Maggiar in Paris, we comprise seven full-time experts in African and Oceanic Art, all of whom are very well-versed in provenance research. In addition, we have a far-reaching network of art historians, lawyers, and researchers in all corners of the world who contribute to our auctions and private sales on a case by case basis. I can safely say that the depth of expertise we can offer our clients is unmatched elsewhere in the market. There is no doubt that this focus on research is critical for Sotheby’s successes and to our status as leader in African and Oceanic Art, both in auctions and private sales.

Auliso: Where do you see the prices and popularity of tribal art in 10 years?

Schweizer: I think the popularity issue is easier to answer, so let me start there. In my view we are going to see a strong rise in interest in the next ten years and beyond that for many more years to come. Over the last thirty years, major museum exhibitions were staged in the United States and Europe, and permanent installations opened at some of the most important museums in the world, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Musée du Louvre and the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris. All these projects of the last thirty years were established within a larger context that presents African and Oceanic Art as part of universal art and world heritage. A movement that is set to continue.

|  |

The first ten years of the 21st century have seen an increasingly globalized world in which national and cultural borders give way to a global society. In the art world, this means that the relevance and therefore market appeal of individual artworks will be decreasingly defined by regional preferences and increasingly by their appeal to a global audience. In light of the influential role for several of the major art movements of the 20th century, African Art and Oceanic Art have an unquestionably central place in this development. The trend of presenting African and Oceanic Art as universal art like we have seen in museums in Europe and the United States over the last thirty years is a clear indicator of this evolution. It continues with new public and private museum projects in the “new economies” including some of the BRIC countries as well as the Middle East. All of this will increase the public awareness and popularity of African and Oceanic Art in the coming decades.

How this will affect the prices in absolute terms, though, is hard to predict, simply because there are too many uncertainties in the financial markets today that might impact the economy and by extension the art market. However, given the universal appeal of African and Oceanic Art and the broadening of the market into “new economies”, it is safe to predict that the high-end of our field will continue to increase significantly in value, at least in relative terms. In the last ten years, even with all the ups and downs of the world economy, the high-end of African and Oceanic Art has increased six- to eight-fold. However, relative to other art market categories, especially those of universal appeal, the high-end of African and Oceanic Art is still very inexpensive. Therefore it is only logical to predict a continuation of the general trend.

Auliso: Why has Indonesian art not enjoyed wide success at auction?

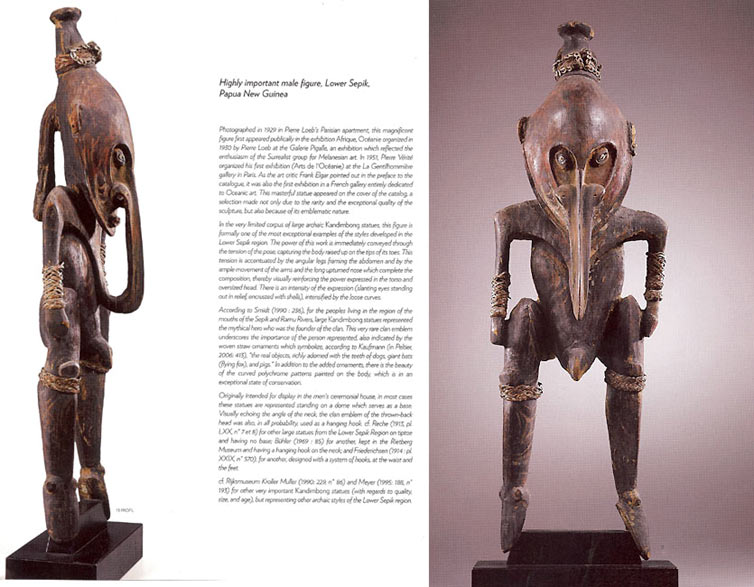

Schweizer: I think it’s due to the scarcity of top-quality material on the public market. Indonesian Art is in this regard comparable to the art of Papua New Guinea. Until a few years ago the top prices for Papua New Guinea Art at auction were between $100,000 and $200,000, and it was rare that one would see such material in the public market. Then a group of blockbuster works from the Jolika Collection of Marcia and John Friede became available for auction. Sotheby’s was very careful not to flood the market with this sudden wave of great works, selling the group over a period of two years from 2009-2011. During this process we established numerous world records, including the current world record for a work of Oceanic Art at auction – the Mundugumor wusear ancestor figure. In earlier times people called such figures “flute stoppers”, which doesn’t do justice to its category and significance, which we sold in New York in May 2010 for over $2 million. We brought many new collectors to the field of Papua New Guinea Art and now prices of $100,000 to $200,000 are more or less the rule for a work of quality, while the masterpieces sell for $1 or $2 million. I think the same thing could happen to Indonesian Art and Sotheby’s would definitely be the best place to build this market. For us it all depends on the supply.

Auliso: Why is Sotheby’s selling notably fewer pieces now?

Schweizer: Well, again back to our international clientele; the category of object that these art collectors seek is very specialized and has very particular aesthetics. In fact, the art they are looking for is in a category all its own. Maybe in another interview we can get to what such works really are, how to define them aesthetically. However, that knowledge of ours is also somewhat a trade secret. Today I will limit myself to telling you only that our international team of experts at Sotheby’s – Jean, Marguerite, Patrick, Alexis, Alex and myself – advises a very powerful group of art collectors and each of us knows exactly what our clients are looking for. The focus of our auctions is to deliver this quality material.

The volume of works sold at auction has been persistently shrinking. In my first year at Sotheby’s (2006) we had to make a strategic decision regarding the New York auction schedule which for some came as a surprise. The decision was to break with a thirty-year tradition of bi-annual sales and cancel the November various owner auctions. Since 2007 we have only had one various owner auction per year, always in May. The reason we did that was we could not source a critical mass of artworks necessary for two auctions over a twelve-month period, especially not since we had already established two very strong sales per year in Paris. Instead, we could find a sufficient number of works for one very strong sale in New York. If we wanted to continue with two auctions we would have had to compromise both quality and our focus on the top segment. Such compromise would have done a disservice to our buying clients, who have very special expectations for the kind of artwork they want to see in a Sotheby’s New York auction. So all we did was to try to understand our clients’ needs and act accordingly. This focus on what is demanded rather than on what is offered also proved to be an excellent business decision: while we have decreased – you might say deflated – the number of lots sold per year at auction by 70-80 percent, we have freed ourselves up to invest four times as much time and energy in the remaining 20 percent of lots we are selling. We’ve seen unprecedented growth over the last five years. We are selling the best works the market has to offer, new world records are set regularly in our auctions, and our transaction volume in New York has grown tenfold in five years. The success of our strategy speaks for itself.

Auliso: What percentage of your sales are “private” versus “public auction”?

Schweizer: Well, we’ve always done “private sales” out of New York. In Europe up until last year, for legal reasons, auction houses were not allowed to conduct private sales. So, I’ll limit my answer to New York since only these numbers are established. By and large I would say private sales make up around 50% of our New York total every year. It is important to know that we do very few private sales in terms of the number of artworks – probably a handful every year. However, these are all outstanding works and each represents an important transaction.

The Haviland Head (left) and The Einstein Mask (right). Both works are truly unique examples and their exact stylistic classification remains a mystery. Originally in the collection of Frank Burty Haviland and first published in 1915 in Carl Einstein’s Negerplastik (pls. 14-15 & 88), both works were sold at public auction in 1936 at the Hotel Drouot as part of the Haviland Collection and subsequently lived in separate private collections. After more than 70 years Heinrich Schweizer reunited them again for the first time in one room, before placing them with their new private owners.

Auliso: Can you talk about any of the pieces or “dollar figures” involved in these important transactions?

Schweizer: All I can tell you is that we always try to find the best quality works for our clients and the best quality has its price. Well, I’ll add that we are currently trying to slightly increase our activities in this area in light of the tremendous competition witnessed in our auctions. As you can imagine, it is very frustrating for a collector who is willing to bid ten times the estimate for an artwork at auction and still can’t get it. And as the competition in our salesroom continues to be extremely strong the same collector can miss out on a purchase several auctions in a row. So understandably these collectors will ask: “Can’t I buy something outside the auction?” We listen and take care of our clients. However, it is also important to know that the decision whether to offer a work privately or at auction is always made by the owner. Sotheby’s does not make that decision. We simply give our best advice as to the potential through either sale venue. In the end there is always a trade-off. In a private-sale you will always generate a price that is higher than the low or sometimes even the high estimate at auction; on the other hand the seller is also running a risk of leaving money on the table, because you simply cannot predict the competition at auction and what final price it can generate. It has to be an attractive deal for both the buyer and the seller. I would say that private-sale prices are somewhere between the low estimate and the projected final result at auction. As we have seen many times over the last years, the final result can be a multiple of the estimate.

Auliso: We’ve seen many pieces of Tribal Art sell for seven figures now. Do you think it is still relatively undervalued compared to other art?

Schweizer: In the bigger scheme of things, once one gets over the mental hurdle that these are not “ethnographic artifacts” but great artworks in their own right, everybody will agree that African and Oceanic Art is on the same quality level as any other major art traditions of the world. So you are right to ask about the potential of this field: considering that a Giacometti sculpture from a series of ten can sell for 100 million dollars, while the top price for an African masterpiece is around 10 million dollars at present, we should wonder how much room there may be above current price levels. For the time being, however, I would say that prices are appropriate for the quality of the art and the stage the market is presently at. Of course, we all hope that there is room for growth, but that depends on a variety of factors. One of the reasons for the strength of the Impressionist and Contemporary Art markets is the great “depth” of those fields in terms of available artworks. In African and Oceanic Art the absolute number of quality works in private hands is simply much smaller than in other major fields. Therefore, you will never have as many collectors of African and Oceanic Art as you have for Impressionist Art simply because there are not enough works available. So the reason that a Giacometti sculpture or a Picasso painting can sell for 100 million dollars or more is that these works are widely accepted assets in very deep markets, which qualifies them as commodities. Many more people on the street will also know what a Giacometti or a Picasso is as opposed to a Luluwa or a Bamana sculpture.

However, one fascinating and extremely attractive aspect of African and Oceanic Art is the availability of top quality works in relative terms, i.e., relative to the total corpus. The relative availability of masterpieces is much higher than in any other field I know. By that I mean the following: in many other collecting fields such as Old Master Paintings, Antiquities, or Modern Art, institutional collecting has been going on for a very long time. Through acquisitions by and donations to museums, many of the best works in these fields have migrated into public collections and are no longer available in the market. In African and Oceanic Art, collecting by public institutions with a focus on art – rather than on ethnography – only started in the 1980s with the opening of the AOA department at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, following Nelson Rockefeller’s bequest in 1978. Before that African and Oceanic Art was owned mostly by ethnographic museums, acquired early on in large quantities from explorers or field expeditions they organized themselves. Because these institutions most of the time didn’t judge the works they owned by artistic merit but other factors such as collection history or rarity, they even sold many important works over the course of the 20th century – just think of what left the Linden-Museum, the Leipzig Museum für Völkerkunde, or even the British Museum. As a result, many of the greatest masterpieces of African and Oceanic Art are still in private collections today, which makes our field extremely attractive. While even with unlimited resources it would be virtually impossible today to build a collection of masterpieces in Antiquities or Old Masters, for example, it is still absolutely possible to do so in African or Oceanic Art.

Auliso: Since some very high profile buyers in other countries have entered the market, I hear from some of my dealers colleagues who feel the market is being artificially “run up” by just a handful of buyers. Is that accurate?

Schweizer: This is absolutely not true. Such rumors only show how little understanding there is, even amongst professionals, about the reality of the international auction market today. We recently ran an internal analysis, asking ourselves how many individual collectors are currently in the market for a million-dollar-artwork from Africa or Oceania. To this end we looked at Sotheby’s sales records since the Robert Rubin sale in May 2011 and counted how many individual private collectors either bought or bid more than 1 million dollars on a single work of African or Oceanic art. The result was 52. And this was only based on our own transactions and not taking into account the sales of other auction houses or galleries. So, the truth is that the current market is very deep on the high-end. The demand for top quality works is not only strong but also very broad-based.

Auliso: Lot 49 from the Robert Rubin sale (New York, May 13, 2011), an 8″ tack-covered Songye power figure, sold for 2.1 million against an estimate of 150-250k. A surprise or not?

Schweizer: This sculpture, a wonderful work I truly love, sold for one of the highest prices in the year 2011, in spite of its small scale, and set a world-record for the category of Songye sculpture. With a result like this there is always an element of unpredictability and surprise. However, it was certainly the best known and most widely recognized artwork in the collection of Robert Rubin; for that reason we placed it on the back of our catalog. We knew what we had. As a relatively small sculpture, in the greater context of what Songye statuary had been selling for before, the estimate was actually not shy. If you keep in mind that the highest price for a top quality large Songye community power figure, about 4 feet tall, had been in the range of 400,000-500,000 dollars at auction, then an estimate of 150,000-250,000 dollars for such a small sculpture was the appropriate estimate. What we saw here was fifteen bidders on this lot in the auction. There was a big “buzz” about this particular lot in the sale. We had also received several unsolicited private offers for the figure before the auction. Savvy collectors who knew it was going to get competitive, did the right thing by trying to eliminate the competition through private offers. Unfortunately for them, the owner of the Estate of Robert Rubin, declined all those offers. Because of the fact those offers were made, we could see long before the auction that some people were going to go after it very aggressively. However, I have to admit that we ourselves were quite surprised when four bidders still kept going at a million dollars, and three were still left over 1.2 million. It is very interesting that the bidders on this lot came from all different sectors of the art market. The direct under-bidder was a long-time established collector of African Art while the buyer was one of the newer collectors in the field. The bidders ranged from collectors of traditional African Art to collectors of Modern and Contemporary Art to collectors of Old Master Paintings and Antiquities.

Auliso: In terms of your personal tastes, what was one of your favorite pieces in the May 11 2012 various owner sale or among the Werner Muensterberger material?

Schweizer: Well, we had an extremely strong selection this year, probably the best sale in the last five years. I rank it even higher than the Robert Rubin sale in variety and quality of the material. We had some abstract masterpieces, some naturalistic masterpieces, some iconic masterpieces, some masterpiece miniatures, and we didn’t just take over a collection from someone, but built this selection from scratch. This is an achievement I am very proud of. The core group of our sale were seven lots from the collection of the late Werner Muensterberger, who was a good friend of mine, and it was an emotional experience to prepare this part of the sale. The Luluwa Helmet Mask (New York,May 11, 2012, lot 62 and front cover), of course, was one of the best and most famous works of Congolese sculpture. It is fascinating to know that he paid 12,000 dollars for it when he bought it from Mert Simpson half a century ago, back when that was a huge amount of money. It sold with us for 2.5 million dollars, the second highest price ever paid for an African mask. Both prices show that quality always finds its market, and if you buy at the very top there is always appreciation of value over time. I also felt strongly about the contemporary sculpture by Magdalene Odundo (lot 64) and the Sherbro Stone Head (lot 61 and back cover). In the various owners sale the work that resonated most strongly with my personal taste was the Buyu Male Ancestor Figure (lot 192). The perfect merger of Cubism and spirituality, it is one of the great masterpieces of its genre. As you might know this work was once owned by my friend Philippe Guimiot who is now 86 years old. When I spoke to him after the sale, he told me he was very proud of me, as I had done justice to a masterpiece. This was the greatest compliment he could give me.

Heinrich, a very special thanks to you for your time, candor and comprehensive answers!

Michael Auliso