Interview conducted and written by Michael Auliso and republished here with his permission.

John standing in a corner of his vast living room next to a Ramu River figure acquired from Verite prior to the sale

TM: What was it like going to New Guinea for the first time?

We went there in 1981, my two daughters Marsha and myself. One of our daughters had beenworking there, as a Marine Biology Researcher on the North Coast for aboutthree months.I had been collecting the art of New Guinea since 1965 or 1966, so it wasnot that the collection was inspired by the trip, in fact it was kind of theother way around. It seemed unbelievable that so many cultures, so manylanguages, so many styles could be so close to each other; and in a sense Ihad to see it on the ground.

What I learned in New Guinea was that not onlyis it absolutely true that within shooting range you have essentiallydifferent countries even though there may be only 300 to 600 people in anyone area speaking a different dialect. There were many different fightingtribes in what is now the town of Brussels. There were thousands oflanguages in North America, when the Native Americans were the only peoplehere. New Guinea continued that tradition up to less than 50, certainly lessthan 100 years ago which makes New Guinea for me a very interesting place as an example of the ancestry of everyone.

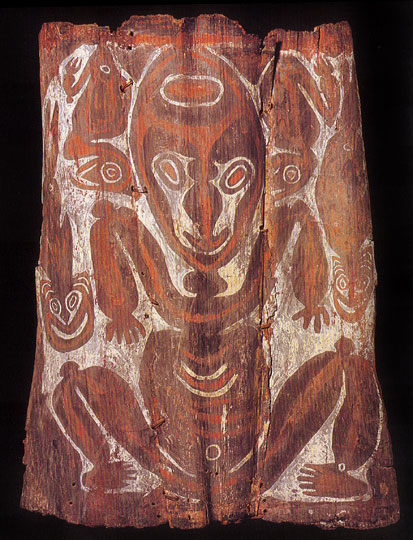

Plate 116. Painting of a Splayed Female, Lower Sepik, Keram River, Kambot People, Sago Palm, Pigments and Binding, 39 3/4 inches

The following images were taken from “New Guinea Art, Masterpieces from the Jolika Collection of Marcia and John Friede”, The Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, Copyright 2005

Another thing that I learned in New Guinea is that the extreme activeness of the carvings and the color is completely consistent with the look of the place. The old story is that when Gauguin went from Brittany to Martinique,and to the south pacific his eyes were opened by all the color. I have been to Hawaii, and Hawaii is black and white by comparison to New Guinea. You’re right on the equator, high humidity, unbelievable active forms, the vegetation, colors of the flowers, if you made modest quiet pieces, they would be invisible there.If the Dogon material is appropriate for a desert environment, then the expressionist material is certainly appropriate for New Guinea.

I also met the people, who are lovely people with the exception unfortunately of the early rascals who were there in ’81, who are now more prevalent, essentially urban kids who were dispossessed by the west, so if anybody gets credit for the rascals it’s us, not them.

I love New Guinea, both my daughters and my wife loved it. We didn’t get sick, which is also nice, because so many people have malaria. I haven’t been back, and one of the reasons I haven’t been back is that it became much more dangerous quickly after that, in terms of criminality, not in terms of savages boiling you and serving you for dinner. I don’t want any bad experiences with New Guinea, I love the art, I love the people, and I show I love them by having them come visit us in San Francisco, where we have an active program to bring New Guinea people, artists, and so forth. Maybe I’ll go back at some point.

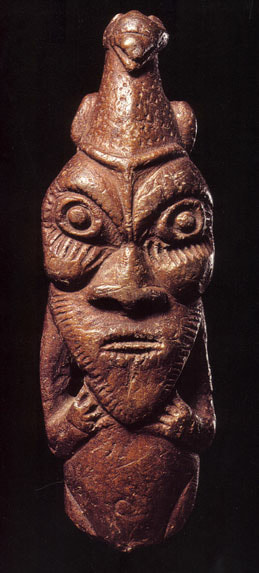

Plate 5. Amulet, Upper Sepik River, Entry of The Wogamush River, Steatite, 4 3/4″ inches

TM: Wayne Heathcote was your guide in New Guinea? Oh yes, Wayne was a superb guide. I learned a lot about Wayne on the trip. The local people loved him. His name was “master big dog” because he had a huge German Shepherd. He towered over the people. I mean two of them together were his height, and they trusted and loved him which meant that he was not exploiting them when he was there. Wayne is a very aggressive dealer, but Wayne is a salt of the earth guy.

Traveling in New Guinea is tough, it’s hot except when you are on the river in an outboard, and it’s pouring rain, then it’s freezing cold. Wayne was always cheerful, he would stand in the back of the boat reading a cheap pulp novel, and tearing off one page at a time, as he read it, so that theoretically one could find us way up the Karawari River, by looking at little pages from a western, although nobody did find us that way. Without Wayne it would have been a terrible trip. We would simply have been buying bilums and shell jewelry.

Fig. 13. Wayne Heathcote on The Sepik River, 1981

TM: Can you comment on the effect that your interest in New Guinea Art has had on the market in the US and overseas?

When I complain about prices, the people who are selling me the pieces, say “yes but it is your fault”. I don’t think that’s completely true. But it is certainly in part true, because these things were not cared about by virtually anyone, when we started collecting in 65. In Europe I don’t know the scene in 65 because I wasn’t there, here when Nelson Rockefeller had bought his things he stopped. Raymond Wielgus, a very famous collector, who has given his collection to the Indiana University Museum, had bought his things, but he sort of stopped too.

Great material was available, it was possible to buy pieces for $100 which is a good thing as a beginning collector, because you make a lot of mistakes and they’re not tragic at $100.Today a beginning collector might spend $10,000 for his first piece. That becomes a tragedy if he finds out later it’s not what he wanted. I think I pushed the price level, but I’m not sure I push it up entirely by paying more.

One of the things that we have done is that we have shown how great the art is. It was not possible to know that before. The museums that showed it were basically anthropology museums that showed specimens, in bad light, they didn’t necessarily show the good ones anyway. The valuation in this art will never be like the valuation in impressionist or post-impressionist art, because the market is much smaller. When I started collecting, after we had 250 to 300 pieces, our collection was worth about as much as a pretty good Cézanne watercolor. That’s ridiculous. Today it’s worth about as much as a very good Picasso. Since a very good Picasso is so ridiculously overpriced, I won’t say it is ridiculous anymore, because now we have to pay that price. But if you think about it, the body of creation, by what is certainly one of the most creative groups in the world, the infinite variety of 1200 languages, and therefore 1200 different art styles at the very least, for the price of one expensive painting from the west, is still ridiculous.

Plate 287. Mask, Upper Sepik River, Hunstein Mountains, Bahinemo People, 22 5/8 inches

TM: Would you say the prices for great pieces are reasonable or unrealistically inflated?

The sellers are running ahead of the market, at this point, so I would say they are unrealistically inflated. Some sellers see prices like the Verite prices, actually they are African prices, not New Guinea prices. A seller whose looking for evidence can choose it very selectively and doesn’t care about that. Also, the sellers tend to overestimate the quality of their pieces, relative to some other piece that may have commanded a high price, but isn’t really as good. But you can buy great things still. It’s certainly way past the point where you can consider this to be a good speculative investment. Anyone who buys art that way, except maybe the contemporary art players, who are really more players than collectors in my opinion. Anyone else is kidding themselves, the spread between the purchase price and the sale price is at least 100%. So if you buy something for $10,000, it’s doubled in value, you can still get$10,000. Because you don’t get the rest, somebody else does. Now of course if you want to wait 30 years, you can get $100,000 shall I say, but you can also get that with IBM.

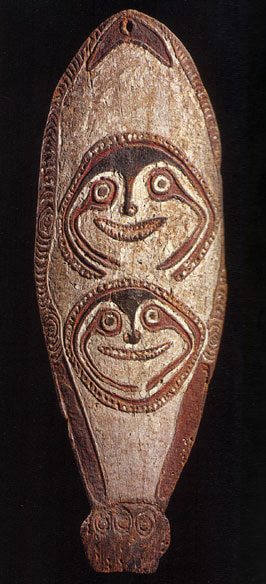

Plate 458. Spirit Board, Gope, Gulf Province, Era River, 53 3/4 inches

TM: Are there any areas of the market that remain undervalued or undiscovered yet?

Oh definitely yes. Wealthy collectors tend to buy important pieces, that’s because wealthy collectors are not necessarily informed collectors. To be wealthy is to have made your money in some field where you can…make money. Being a collector does not lead to money, being a venture capitalist or hedge fund operator or something makes an enormous amount of money. The business mind and the collector’s mind are quite different. The business mind always thinks of return on investment also always thinks about Iconic major pieces which have a premium. Fortunately, I’ve lived long enough to have known some of the old group of collectors, some of whom I met just recently in Germany. They were never wealthy, they bought exquisite, shall I say in the mind of the ignorant, unimportant pieces. Exquisite, unimportant pieces are still a screaming bargain. But you have to be specific, for example, a wooden carving is worth infinitely more than a bamboo object. Clay… terracotta is an area that we have been collecting very actively, because since we are building a museum collection, I want to have representation of all the things they made not just the smaller group. Actually the clay are mostly made by women which is also very important in a museum collection. Similarly, the fiber pieces, the bilum bags… You can buy an absolutely superb bilum bag for $600 handmade by a woman in that knotless technique that they have there. 50 years ago you could also buy a piece of junk for $600. So it’s important that you learn before you start spending your money.

Collectors who are not trying to build an encyclopedic collection like this, which I don’t advise, because there are so many categories that are unavailable, but who simply want to have some beautiful things in their home can find many a thing in New Guinea, perhaps even more things in New Britain because nobody collects New Britain. I don’t know a single person in the world who collects New Britain. New Caledonia there are more collectors. Solomon’s…I know of only one who’s truly serious.

Plate 333. Pottery Trumpet, Taul, Upper Sepik River, Washkuk Hills, Probably Kwoma People, 12 inches

Plate 582. Bamboo Container, Eastern Highlands, Lamari River Area, 11 inches

Unfortunately, the minor things are hard to find because the dealers don’t mark them up much because they don’t have a very high base to start with. It’s the same amount of trouble to sell you a $25,000 figure, as it is to sell you a $600 bilum. But I would advise people to do a little traveling. In Europe, they’re still available which brings me to a point I want to make whether or not you have a question. The most important thing in collecting is knowing the material. It’s also useful to have the money to pay for it.

Money if anything is a distraction because if you really have lots of money, then you think it doesn’t matter to know, because after all you’re so smart, you made the money. That’s not true. You have to handle the pieces, you have to see the pieces, you have to talk to the people in the museums, and ask them to let you see the reserves. In some museums they are very generous, I was with the curator in Berlin for two days, of course I’m famous, so maybe he gave me a little bit more time. But I know he shows pieces to people who are not so big a deal. Curators like pieces, and they want to impart knowledge. They’re sort of professorial in their style.

The material that’s going to be in the study collection at the de Young is only called a study collection because the gallery is too small. It’s every bit as good as the stuff in the gallery. All of that will become available although not for 10 or 15 years because that’s a huge construction project.But for the future that will be available. Also there’s more and more material from museums on the web. Really to see things in your hand, or in your glove as they now require, is essential. Without that you don’t know what you are doing. That’s a big problem.

TM: In your quest to build a well rounded collection how many pieces have you acquired since you began?Oh well, I don’t really know. I would say we have probably 5000 or 6000pieces now. I would say we acquired another five or six hundred that we no longer have. I would say, then my wife Marsha would run into the room and say “Oh no you Don’t!” I might acquire another thousand pieces. That could include tiny little nose ornaments, and one or two absolutely mind boggling superb things. Although I must say the mind-boggling things are basically all gone. There are a few private people that have kept a small number of those. Smart, because they are selling at the very high market now. Not so great for me, but that’s life.

Plate 201. Pigment Dish, Middle Sepik River, Iatmul People, 8 7/8 inches

PART 2

John and Marsha Friede in their yard standing next to an enormous New Guinea Highlands Telefomin house door board

TM: I know that expanding public awareness of New Guinea Art is important to you. How close do you feel you are to transforming the art worlds perception of the art? Do you feel the old bias is slowly vanishing with your exhibition at the de Young Museum, and the publication of the Jolika Collection?

I don’t think there was a bias against New Guinea art, I think people were just ignorant about it. There was a certain bias, because this is the quality I like best about it, it works for some people the other way. The New Guinea people were isolated from the rest of mankind for almost 50,000 years. They migrated from Africa, they and the aboriginals were the same group of people, and maybe little groups spun off on the way and became the Naga, the Hill Tribes of Southern India. There’s a possible argument that even the Ainu are part of that movement. The genetic work hasn’t been done yet and we don’t know. We do know that the New Guinea people arrived first in Australia, not in New Guinea. They walked to New Guinea, the Torres Islands were a plain, more or less the way the Siberian plain occurred 40,000 years later. There were ice ages back 50,000 years ago and they just walked there. But when they arrived, it was very different from Australia, and then the ocean rose and they were alone. It was a jungle, Australia is a desert. The art, the culture evolved from that, but it did not evolve with the rest of the world.

When you collect say the art of Africa, you’re talking about an art which was part of the world. That doesn’t mean that the King of Zaire in the year 1500 was familiar with Paris, but he had familiarity with modern technologies, with iron, with metal. Perhaps with Arab slavers that had been there at least 1000 AD, there before there were even Muslims and all the integration into the world, so they were somewhat familiar. Our stuff is very unfamiliar.Also, they are acknowledged cannibals. We probably all were cannibals, but some of us are a little unwilling to admit that.

In New Guinea it’s part of the right of initiation, as it is in most of the places where it exists. Also it’s strong, my mother had some beautiful African pieces among impressionist paintings. If you put some of my New Guinea pieces in the house the way Bill Rubin did in his primitivism show at The Museum of Modern Art they would eat the apartment. They are so much more powerful. They would make the people accustomed to the more gentle and civilized styles very uncomfortable.

Plate 267. Male Figure, Yimam, Middle Sepik, Upper Karawari River, 36 inches

I have always been a propagandist in the same way the young lover proclaims to the world how wonderful his girl or boy is, I proclaim to the world how wonderful this art is, and I have been fortunate enough to have found a partner in the museum who feels the same way. Very few museums would have given the scale of gallery that we had, installing it all themselves, without asking me to pay one cent for it with the best fiber optic lighting, and display cases I have seen in any museum.

By some miracle of good fortune we were able to hire Christina Hellmich who had been the Oceanic curator at Salem, Peabody Essex at Salem Mass. and has now become the curator of the Jolika Collection and Oceanic Art in general at the de Young. She is a fountain of ideas, a geyser of ideas. She has been very much involved, as I have been with the political side of New Guinea. The ambassador to the US and Canada, a young man named Evan Paki who is in his 30’s, but of course with an advanced law degree, is one of the most educated people in New Guinea. He was enough of a decent citizen to turn down the partnerships that he had somewhere in Australia, to become the ambassador for what has to be a very low salary. He is tremendously enthusiastic and has said what we have done essentially is opened a PNG showroom in San Francisco. It’s a nice place for it.

It is! The San Francisco people are remarkably open-minded. I come from the east coast, and the east coast is much more Eurocentric. The Boston museum didn’t have any tribal art until recently, and they have a small collection from a nice man named Bill Teel & his wife. The Metropolitan took the primitive art museum because Nelson Rockefeller was Nelson Rockefeller and said “you will take this collection”. They always hated it, although now they are starting to realize it is not to be hated, and it can be a draw, but they still have not really capitalized on it. It’s the kind of stepchild that I would never want my collection to be.

We have, as I mentioned from Christina, many programs. We try to include the contemporary art of New Guinea in the programs but not in the collection. About the artists from New Guinea, we just had a show and a demonstration and performances with some people at the very end of April, in San Francisco and a big crowd came. Ninety Percent of those people two years ago wouldn’t have known where New Guinea is. In fact, my favorite funny quote from Evan Paki was “I’m glad you are doing this, because I get so tired of answering the question is New Guinea part of Africa?”

Plate 138. Figure for a Sacred Flute, Wusear, Lower Sepik, Yuat River, Biwat People, Wood, Cassowary Feathers, Boar Tusk, Human Hair & Molars…, 17 5/8″

TM: What are your plans for the future?

My plans for the collection for the future is that every good thing will go into the de Young. I don’t say everything, because there will always be pieces that are weeded out. The de Young has a limit as to what it can show, and if I have a great one and a not so great one, it is better to return the not so great one to the market and maybe pay a quarter of the price toward something else. But that’s immaterial, the collection will go there. I hope I am successful enough in my venture capital investing to provide endowment, so that the program side will continue to be very active.

In terms of publications, we did the first book which was intended to be an overwhelmingly impressive book. I felt I had to make the point, this is a great place, this stuff is fabulous. That book was a generic book that covered the whole area of the collection. It will be followed, assuming I continue to walk the earth, with seven to nine more books, which will be regional books. The first two books are pretty far along in preparation, and relate to the next rotation of material that will take place at the de Young.

In 2009 the present exhibition will come down, a few super New Guinea pieces from all over the place will remain up, as an illustration of the cultures of the island. Then a large exhibition of highlands and Massim material will go up. We are currently doing a Highlands book and a Massim book. They will both be approx 500 pages, with approx 350 color plates with good serious essays by scholars. That will be followed by other books, I haven’t figured out the order, and of course New Guinea is a place where everybody influences everybody so whatever arbitrary line you put on the map, you’re wrong.

Plate 502. Ceremonial Mask, Buk, Torres Straits, Turtle Shell, Wood, Cassowary Feathers, Shell, Seed, Natural Pigments, 31.5 inches

The Sepik is too big for one book, we’ll have to break up Sepik into two groups. I want to do a book on the Ramu River, no one has ever done a a book on the Ramu. I want to do a book on Astrolabe Bay, Huon Gulf, and Collingwood Bay. Also a book on the Northwest Coast (Lake Sentani, Geelvink Bay) and if I can fit it in, we may include the west and south coasts of West Papua (Asmat, Digul and Marind-Anim). The one book that I think is going to be an extraordinary revelation is the PNG south coast. We will start with Moresby and Motu going all the way to the Torres Straits. Obviously we have Australia in there but I don’t care about politics. That will include the classic Papuan Gulf material, the Gogodala material, the Fly River material and Torres material. Theoretically it has a title like “The Masters of Surrealism”, and there’s nothing except some of the Baining tapa masks of New Britain, which are actually part of the same ancient culture, there’s nothing to touch that stuff for complete wild madness. Of course it’s not madness, its man’s incredible imagination. We all have it, but there it ran free. I think that’s a great thing.

If the world looks at this as the art of some strange, perhaps smelly foreigners, they are missing the point. This is one of the primal art image sources in the world. Take the ancient Alaskan cultures that were on the edge of the glaciers as opposed to the deep jungle. The terrain was different, so the hunting was different, but the magic was the same. A lot of the objects were the same. The spear thrower weights were made of mammoth ivory not bamboo or shell, but they had the same function. They did more painting than they did carving, because they didn’t have much in the way of wood. The glaciers hadn’t left them any great forests. Unlike the glaciers, you could go there in my life time, and take pictures of them. The entire culture is on film, and that’s amazing.

Plate 452. Female Figure, Imunu, Gulf Province, Iwaino People, 24 1/8″

TM: Will you continue to expand your collection?

Yes I will continue to expand the collection, assuming that I can honor my responsibilities to the children. We called it the Jolika Collection, because that’s an acronym for the children, JO–Johnny, LI–Lisa, and –KA for Karen. The collection’s very valuable, but children of wealthy people are greedy little bastards, and would have been very upset that Daddy is giving away all that money. They wouldn’t think of it as art, they just think of it as money.

My kids took the opposite point of view, they would have to keep a few things, but they understand that you can’t give away Mount Fuji and just keep the white part on top. Then you don’t have Mt. Fuji. So you have to do the thing right, or not do it at all. They also understand that there’s a physical, financial and psychological burden in having a huge house full of stuff. Kids today would like to be free of that, and it’s nice the museum is providing that space. One of our children is a doctor in San Francisco, and her kids are right there. One of our other children is a resident of Seattle and while that is not right there, it’s close. Our son is in New Hampshire, so he’ll have to take a plane to visit his sisters out in California. After it gets really cold in New Hampshire, he may want to do that from time to time. We just built a house in Berkeley California right next to our daughter’s house, which is fun, and it’s a place for all the kids to stay.

In terms of targeting what we’re going to be buying now, it’s clear over the last year or two, as I become more aware of the space limitations in California, I have tried to eliminate the middle ground to the extent that I can. This is a problem for us. Douglas Newton and I used to talk about this. We like everything from New Guinea, we may not like the whole statue but we like the nose, the elegant way the feet are, you know you can go on forever. But you can’t collect forever, because these things just stack up.

Plate 270. Female Figure, Aripa, Middle Sepik, Upper Karawari River, Ewa People, 42 inches

So I am basically buying things in the higher price category, those things that absolutely demand to be in the collection. Sometimes they force something else out, if they aren’t part of a group. If nothing else looks like that; it’s even more interesting in a way. I try not to ever buy seconds. There are certain types of things we don’t have at all. This is not because we don’t like them, but because we have never seen one as good as the one I would like to have. It’s not a stamp collection, so we don’t need to have all the colors of the 14 cent inverted airplane stamp. If a piece isn’t up to par, it cheapens the collection. Another thing collectors have to be careful of is that you don’t want to buy one that looks just like the one in a book. It may look more like the one in the book than you would like. They guy who made it may have had the book.

The other kinds of things that we are buying, that I think adds a tremendous amount of value to the books we are publishing and to the collection, are the absolutely minor things. The everyday objects. Everything in New Guinea has some symbolic or ritual meaning, even a pounder, that has a face on it, to make it more effective as a pounder. You can clutter up the world with those things, but if you are very careful, you can get wonderful things. You get 3 or 4 of those, and the major figure, and you’ll get a better understanding of the culture, than if you just had that major figure. Even the minor pieces can be hard to find, but they are still buyable, so all you reading this should buy them too. I’m not pushing the prices up on those because they are so low already and I like to leave them there.

Plate 85. Headrest, Lower Sepik, Wood, Bamboo, Shell, Fiber, 18 3/8 inches

TM: What do you see in the future for New Guinea Art?

Well New Guinea was a place with a small population of three million people maybeless. There aren’t very many pieces. Now you think there are; I was in Berlin looking at the store rooms, they have a lot of pieces. But how many really wonderful things are there 2000, 5,000, 10,000? We read that the Field Collection in Chicago they collected 80,000 objects, I’m sure it is a lot of relatively undecorated sticks among them. I don’t think there are 80,000 wonderful New Guineaobjects in the world. That includes the little ones. They’re all getting bought. At some point, sooner rather than later, New Guinea art is going to be more like Romanesque Art, than it is like African or contemporary art. Every year you have more contemporary art. You’ll be able to buy a piece, I can go out today and buy a Romanesque Capitol, but you want to buy a Romanesque collection? Forget it. If you get 5 pieces in 5 years you’re lucky. It’s not that expensive either. When you have no pieces, you have no dealers and no collectors. If anything the prices go down.

In the case of New Guinea Art there’s enough pieces that I don’t think the prices will go down. I don’t care. When I buy a piece, the next click on the value chart is zero. I’m giving it away, and I can’t even deduct this stuff because it’s worth so much more than what I will ever earn in my life. The tax consequences of the gift are also zero. When you leave things in your will to a museum, you have no tax consequences. A lot of pieces will be left in our will, because we want to live with them as long as possible.

As you said when you walked in the house if you have 30,000 spirits you’re liable to live a long time, maybe two of them are actually pretty good for longevity! There might be one trying to kill you, but I like to think the majority are on our side (laughter).This is great fun this collecting, it’s changed our lives.

Plate 329. Ceremonial Carving, Yina, Washkuk Hills, Kwoma People, 28 5/8″

Link to de Young Museum and the Jolika Collection

Michael Auliso and Tribalmania extends its sincere gratitude and appreciation to John Friede for offering his time and insightful views!