Interview conducted and written by Michael Auliso and republished here with his permission.

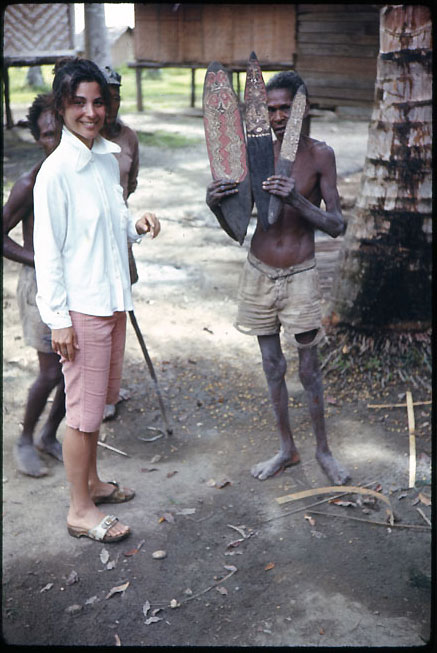

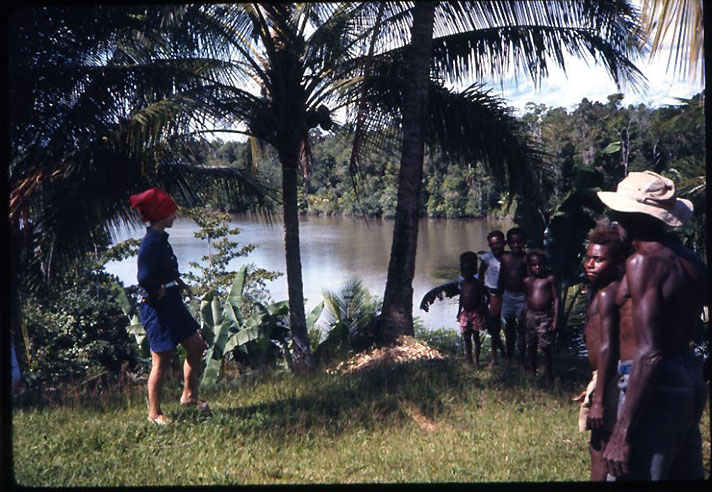

Field photos taken in New Guinea, Madang Province in 1967

TM: What first attracted you to the tribal art business?

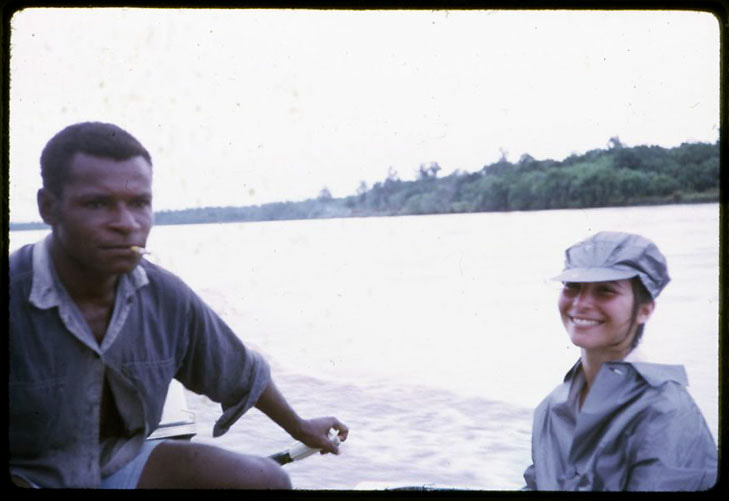

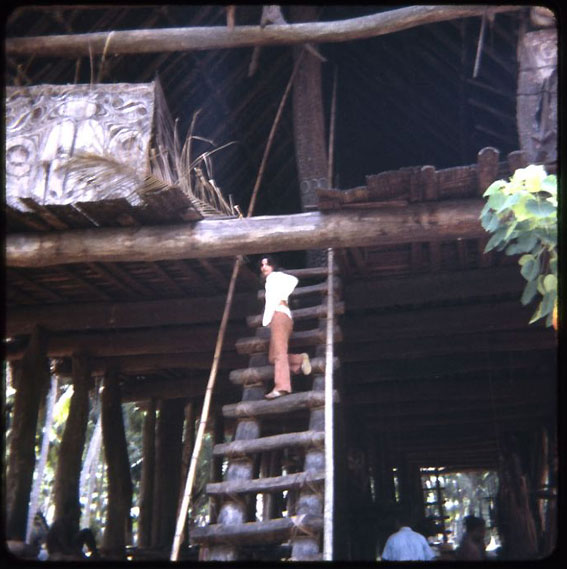

During WWII my father was stationed in what was then the Western part of New Guinea, now called West Irian. He used to tell us stories about White Beach number 3 where his unit was posted. I was doing some research at the Australian National University for a Professor called Eugene Kamenka on the Marxist Theory of the Law. Really I was just a go-for, and used to wander over to the library to pick up books for him and happened to pass the section on Tribal Art where I ended up spending quite a lot of happy hours just browsing. This coupled with the fact that while in graduate school in New York, I had worked for Jerry Eisenberg, who was then a general object dealer on Madison Avenue. Jerry also handled some Oceanic art. The thought occurred to me that I could go to New Guinea myself, collect some objects and sell them in New York. Also it would give me the opportunity to see where my Dad had been stationed. My dad loaned me $1500 to put together a small collection. On that trip, in 1967, I met Douglas Newton and Wayne Heathcote. In those days, the late 60’s, it was completely safe for someone to take off in a canoe with a few guides and travel up river staying at the Missions. I also worked with local dealers like the ex- Missionary Barry Hoare. When I returned to New York someone arranged for me to show the collection to the then Director of Bloomingdale’s and that is where I had my first exhibition of Tribal Art.

TM: How did the early business experience evolve for you?

After the Bloomingdales show I made several trips back to the Pacific and on one of these trips brokered the sale of Wayne Heathcote’s collection to a family from Texas through Walter Randall. That collection was in time purchased by John Friede and today forms the basis of the collection at the De Young. I remember that the commission of thirty thousand dollars which I received for doing this seemed like a fortune. Most importantly, at the beginning of the 70’s, I decided to branch out into African Art and Alain Schoffel gave me the name and address of Lance Entwistle and Anthony Plowright, who were based in London.

Field photos taken in New Guinea, Madang Province in 1967

TM: How do you account for so few women involved in the tribal business, do you see any balance on the horizon?

In the early days it reflected the fact that a lot of the material was collected in the field by the dealers and the conditions were often dangerous – or at least not very comfortable. Conditions which would on the whole have appealed more to men than to women. Also the societies with whom those dealers were interacting were male dominated and they would certainly have found it easier to work with a man than a woman. On the other hand there have always been women active in this field like Hélène Leloup, Patricia Withofs, Christine Valluet, Maureen Zarember etc.

There is also a whole macho thing which relates to the concept of physical exploration of unknown lands particularly in Africa and the Pacific. Many men would really like to go around with a spear between their teeth and collecting is probably the closest they will come to this experience.

There is still an innate bias against women in this field. Do you remember when we first met and you came downstairs to the gallery in Paris – the three of us were sitting there and chatting and you said to Lance “ I wish she (i.e. me) would come and work for me” and Lance had to explain to you that I was his business partner of thirty eight years, not his assistant. At a certain point the bias is too ingrained to try and work against and I do pass clients onto Lance, who I think will work better with a man. I have had to accept that this attitude is built into our society and get on with things. Lance has always been very good about supporting me knowing that this blinkered attitude remains. Two years ago I had an amazing year and sold the Nail Fetish to the Met and the Afro Portuguese Ivory to the Quai Branly and when people called to congratulate Lance he always gave me full credit, but the New York Times said, “Lance Entwistle Gallery.” Bless them!

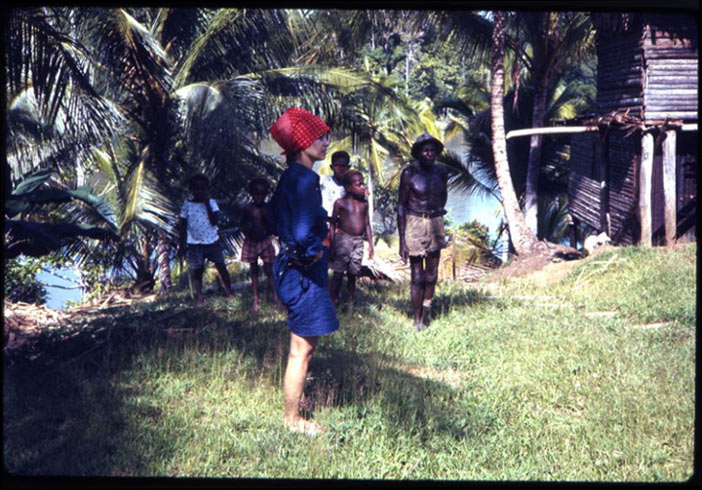

Field photo taken in New Guinea, Madang Province in 1967

TM: Would you say there is a difference in the way women approach the tribal art business? If so, what challenges did you have to overcome to rise to the top, in a field dominated generally by men?

For a partner I have a very charming six foot one male with a great photographic memory, who is intensely scholarly and speaks six languages. He is also very funny and a great story teller which I cannot do to save my life. Our arguments are legendary but somehow we have managed to stay on very good terms for thirty eight years and more importantly I think we respect each other’s judgment of what the other person is seeing even when we are communicating over thousands of miles. On the other hand I definitely prefer more Classical material while he can get very excited about things that are really encrusted with layers of “something”. I am not sure what he would say I bring to the equation but somehow it works.

Being a woman in this field, well there are myriad stories to support my experience by every woman I know, but perhaps an interview with Sandra Bullock sums it up best. When congratulated on the fact that her recent movie was the highest grossing female star vehicle in the history of motion pictures she responded “It’s nice, but it’s odd. It’s like, you’re female and you’ve done this!”

Field photo taken in New Guinea, Madang Province in 1967

TM: Considerable energy must be required to obtain the finest objects, as well as to manage and maintain two staffed galleries in London and Paris. Has dividing your attention and time impacted your life? Would you share some of your methods that allow you to so successfully cope with this much business & personal responsibility?

Lance and I both love the material so admitting we are workaholics doesn’t really answer the question but we do work very hard. On the whole either because of temperament or particular skills I would say that Lance is in the Paris gallery more than I am, a. because he is absolutely fluent in French and I am not. I love travelling and meeting new people and seeing new things. When we started the business we would see marvelous pieces turning up in England all the time. When we were first married we took my parents on a short holiday in Scotland. My mother’s proviso was that we were not allowed to go into any antique shops. On the last day we were going to stop for a Cream Tea and Lance went off to park the car. He came back a few minutes later to say that he had found a Benin figure – to make a long story short in the end we sold it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art where the standing Lower Niger Warrior is on view. On another occasion I was sick and Lance went to view Phillips and came back and announced that the European Mediaeval Hunting horn which was coming up for sale was actually an Afro Portuguese Oliphant. This turned out to be the Drummond Castle Oliphant, published as a drawing in a Nineteenth Century book. The hunting horn had been given by the King of Portugal to his daughter Katherine of Braganza, on the occasion of her marriage. It is a magical object and is today in the Australian National Gallery. Those wonderful discoveries happen very rarely in England today so we have to look further afield. Last year I would say that I was on the road six months of the year.

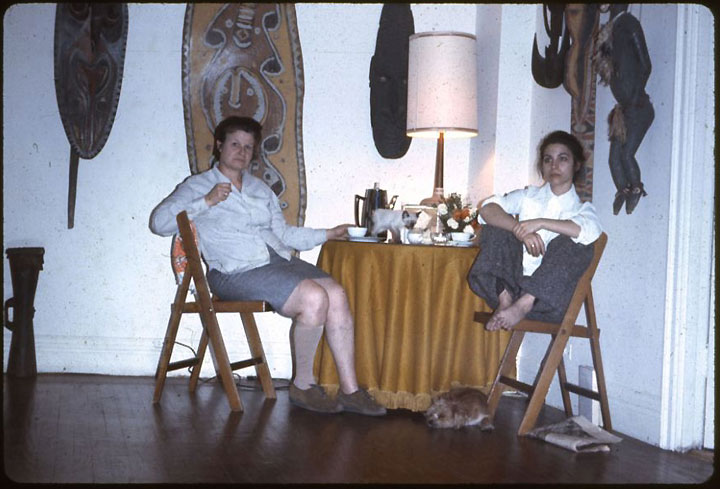

New Jersey 1968, interior home w/ field collected objects

TM: Despite these odds you have been incredibly successful, any advice for women considering entering the field, or those already in it?

Don’t look to the right or the left, just be confident, know who you are, don’t take rubbish from anyone, be well prepared and trust your own instincts.

TM: What is your overall view of the tribal market in view of the current world economy, and what direction do you see the business developing in the next 5 years to 10 years?

The current world economic situation, in spite of the myriad announcements coming from various countries that the recession is over, continues to have an impact on the field of Primitive Art. The upper Middle Class collectors, the Dr’s and Dentists, who used to be the backbone of our business are not as active. The primary buyers now are the big new collectors who are also active in other fields of Art. They bring deeper purses to the market but they are also circling a smaller number of objects at the top end of the market so there is a lot of competition. At the moment they are not yet collectors with a deep knowledge of the field so they are really seeking trophies whose value they can easily access because they have bought the piece in open competition at auction or the piece has an impeccable provenance and publication history. In our experience as they become more experienced they realize that they do not always end up with things which are the best in the field by buying at auction no matter how high the numbers are. Often when this “eureka moment” occurs they will turn to trusted dealers to act for them and ensure that they really do acquire the best.

We have filled this role for George Ortiz, Morris Pinto, Bill Ziff and many others; and, also, over the years with the more active museum collections like Dallas, The Metropolitan Museum in NY, and the Nelson Atkins in Kansas City. I hope that the collectors of medium priced objects come back to the field because that is where the fun is; in pitting ones aesthetic judgment and knowledge against other buyers in the ring.

Selling a great thing is more often a matter of price rather than judgment; history has already assigned a place for the great object so it becomes a matter of who will reach for it. With less well known objects so many other factors enter into the experience it’s truly a terrific high. I would also like to point out that we have always believed that there are great things at all price levels as price is mostly determined, after rarity, by fashion, and that can change so you can bet against the market similarly to approaching stocks. What we are always looking for is quality even if it costs a few hundred dollars.

Field photos taken in New Guinea, Madang Province in 1967

TM: In our business there are not many enduring partnerships. What makes your relationship with Lance work so well?

We grew up and developed the business together over thirty eight years. Most of the time we speak with each other (or today communicate via email or SKYPE) every day. That kind of dialogue builds a commonality of attitude towards the material and business practices. Also no matter how intense the discussions we know that we will always pick up the conversation as we share children and now a grandchild. We are very lucky that on the whole we share a wonderful extended family: Lance’s wife Marianne Holtermann and my husband Colin Hand, and our children Redmond, Sarah, Maia and Olivia, and now our granddaughter, Leni Broomberg. They are all very close to each other and to us. We also have a tremendous staff: Francesca Martelli, who runs Paris, and Katherine Rea, Christian Elwes, and Diane Wilson in London.

TM: How much has the economic downturn affected your business model? What changes in strategy have you made, or do you plan to make?

We work harder! What we tell our clients is to buy the best they can afford and not to make impulse purchases. Like real estate where the mantra is always location, location, location, in art the better objects always experience the greatest appreciation in value. We are also planning to do some publications as we are both very bookish people and are looking forward to the exercise although I am sure there will be major and very loud discussions about what the front covers should look like.

TM: What advice would you give dealers and collectors considering the economic condition that exist? Is there any “Smart” way to buy art these days?

Look for areas which are not fashionable like Nigeria, concentrate on seeing as much material as possible. Treat your dealer like a stock broker and make him a friend. Most dealers will bend over backwards to help a client who appreciates the service they receive towards building a collection. Buy less and more carefully. Do your research before leaping. Don’t be afraid to prune things in which you have lost interest or which do not come up to the aesthetic level you now know to be the level to aim for. All the old adages still apply – condition, aesthetics, provenance, and price. And take the time to enjoy the companionship of the wonderful people in this field it will lead to some lifelong friendships.

Tribalmania extends its sincere gratitude and appreciation to Bobbie Entwistle for offering her insightful views.