Interview conducted and written by Michael Auliso and republished here with his permission.

(Note: This interview was conducted in November 2008 at the Carlyle Hotel in New York City. We thought it appropriate to release such a special feature to our audience in celebration of the opening of our new ocean front gallery in Half Moon Bay California)

Lance in his gallery on 5 rue des Beaux-Arts during the 2006 Parcours des Mondes Fair Paris

TM: How did you begin selling tribal art?

It was really happenstance. It began when I left the University of Oxford where I had studied oriental languages. I had no immediate career prospects but I started working for a friend of my mothers in a gallery which was selling mostly things that came form the Middle East like ancient glass, Islamic tile work, rugs and icons. In the course of hunting down some of these things from British sources I became exposed to tribal art. I saw what seemed to me to be wonderful things that could, in some cases, be acquired for very little money. Since I had very little money it seemed to make since to buy them and to capitalize myself by making discoveries. I began with a booth in the Portobello Market which I inherited from a fellow I worked for who had a gallery. It was kind of a low-end retail outlet and he had tired of the Portobello source and handed it over to me. After that it was really prospecting in the “British bush” or what I call outback looking for things in junk shops and so on is how I got going.

TM: Can you describe your relationship with Bobbie and what makes your partnership so successful?

I met Bobbie fairly early in my career and had her lined up as a client. She was working in New York and I was working in London. At the time I guess New York had a kind of a romance to any beginning dealer. It seemed it was a bigger pond to play in than London was. So when I heard there was this rather beautiful dynamic dealer operating in New York, I and my partner suggested that we get to know her. One thing led to another and we developed a personal relationship, I think very early on I realized apart from the personal chemistry that she was an incredibly dynamic energetic person. I was naturally very retiring and rather shy. The idea of cold calling made me break out into a cold sweat whereas it didn’t matter to Bobbie.

What synergies are in play?

I’m quite methodical and structured in my thinking and the way I organize things and so I was able to give some kind of “shape” to her energy. But I have to add, Bobbie is a very good strategic thinker and very good at seeing the big picture. I’m not a detail man so I think there was as you imply a synergy there. That’s continued to be the pattern of our dealing. Bobbie has another great quality, which to some might be considered a defect, but she is not very interested in the fine shading of nuances between a good piece and a slightly better piece. What she is very good at is grasping the importance of a great piece and going for it. I tend to see the shades of grey, the gradations all the way up the food chain if you like. She’ll be more focused on the high-end and on the very significant things which are very positive in my view and at the end of the day is what defines the really top dealers. You know, how often to they get their hands on something really great and what do they do with it? She certainly has a great history of coming home with important finds and delivering.

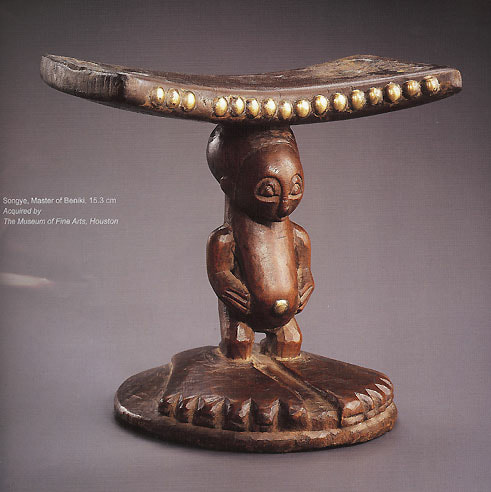

Afro-Portuguese Benin saltcellar, 16th-17th century

TM: Bobbie tells me you speak 8 languages. What are they and why do you think you have such a facility for learning difficult languages.

It is hard to claim any great virtue from speaking foreign languages. My first language was English but I had the advantage of learning my second language which was French at a very early age. I also speak German, Italian, Portuguese, Indonesian “Bahasa”, Arabic, Farsi and Spanish. I learned Portuguese at the time of the 25th of April Revolution which was the time when the Portuguese colonies achieved their independence. There was an exodus of native Portuguese back to metropolitan Portugal. It was a time when we thought there would be opportunities and it turned out there were, as were able to buy some very good Angolan origin pieces. That’s why I learned Portuguese specifically in the service of the business.

When I learned Bahasa Indonesian it was also as an adjunct to the business. Early on we when on a field trip there, which was incredibly good fun but probably was not the most profitable. It was a great experience, it was genuinely field work and we went into the villages collecting textiles from their original owners. Very often when people tell you they go into the field, actually what they do is go to Bamako or wherever and buy from the dealers, they don’t actually go into the villages. When you do go into the village it is a great experience and very enlightening. As it turned out even our guide and translator frankly didn’t speak English so it was not much help to us. Indonesian is an easy language. Anyone who applies themselves can learn enough Indonesian to go into the jungle in three to six months. It is a very simple language.

I think if you learn a second language young, it kind of de-dramatizes the issue of language learning. I think there is maybe some inherited ability in the ear maybe just the way people have a musical ear? I used to enjoy Latin languages, but I have to say that learning a language from scratch these days is my idea of hell because of the limited amount that one can communicate. I’m impatient today– I want to be able to say the things I want to say and quickly. So having to learn the “cat is out on the mat” or “which way is to the railway station” in a new language is rather tedious today. Whereas now I enjoy developing the ability I already have in some other European languages. I did study oriental languages but I never really used them. The European languages I’ve studied I’ve used and they have proved very useful to me. I find them particularly useful in terms of straddling continental Europe and the Anglo Saxon world. I’m able to speak to my French clients in French or to my French suppliers in French to my Italian clients in Italian, Germans in German. It adds a meaningful dimension even if sometimes we actually conduct business in English; when we get down to the nitty-gritty people are more at ease speaking their native language. It establishes a different level of rapport than if you’re always forcing people to speak your language. You have an immediate warm reception if you speak people’s language.

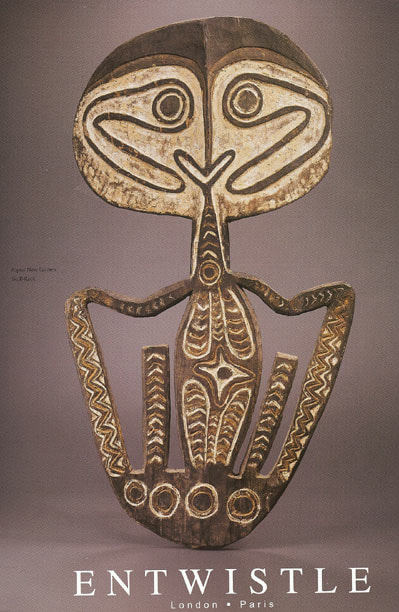

New Ireland Malagan Figure

TM: You’ve created a distinctive mystique about “Entwistle Gallery” which few other dealers have achieved. How was that possible?

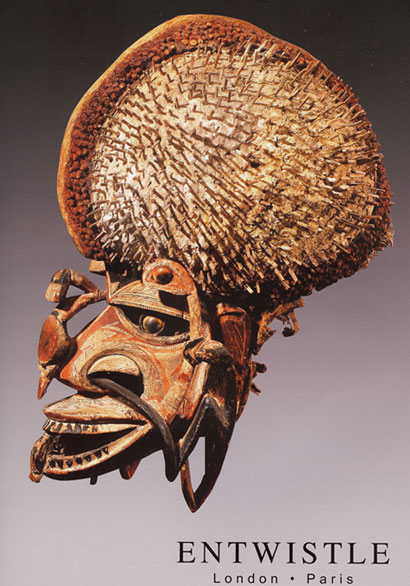

Well it is very nice to hear you say that we’ve created a mystique, I was not that aware of it. I think the truth of it is that the market and the marketplace is pretty pitiless. You stand or fall over the years by the deals you’ve done and the relationships you’ve created with your clients which keep you in good step. It is a very hard business to have a meteoric rise if you like. While you may do well commercially, establishing relationships is a very long and arduous business. Even though we’ve had early recognition as “guys to watch” the actual long-term solid reputation comes from the actual pieces that you’ve sold and the reputation of those pieces have, followed by the endorsements that their owners give you over the years. That kind of word of mouth thing takes a long time to establish. We certainly did do some strategic things early on which I think helped to establish our reputation. For example, when we began to advertise, instead of advertising inside African Arts where there was a very mixed bag, we noticed that the back cover had been occasionally used for advertising. When we joined the magazine it had been used for editorial. We asked them how come they no longer had advertising on the back cover and they said there weren’t any takers. So we made a three year exclusive contract to get the back cover. That kind of set of apart. We advertise as if we were a brand promotion rather than a point of sale. So we began by putting an object and a long spiel about the object. Then we reduced the spiel to a simple caption but we always put the name and address of the gallery. We then actually got rid of the address details on the basis that we were not trying to sell an object but to sell an image of ourselves. Of course today you can do that with Google. Back then the downside was that we had people saying; okay these people have some good stuff but how the hell to you get in touch with them? At the time I guess that did create something of a mystique, however, some people felt it was pretentious.

Papua New Guinea Skull Rack

TM: Do you have a key to cultivating such a sterling reputation in the art world?

There isn’t a shortcut to having major objects. This is the most important thing. It should also be said that this business, like many other businesses in a fast moving world, you’re only as good as your last deal. Or nearly, that’s an exaggeration but you have to keep refreshing the perception of you. Either you’re an up-and-coming young dealer, you’re an established mid-career dealer, or senior dealer or ex-senior dealer. The question becomes, yes you have to have great stuff but what has happened to you now? So you have to keep that image fresh. We had the experience in 2008 of selling two world class objects. When we sold these two objects we made a special feature of one of them. With both of them we did a small campaign with museums where we circularized directors and curators of all of the serious museums in tribal art with a package. We included images and history of these and explained how one had been bought by the Metropolitan and the other by the musee du quai Branly. Anybody who had been forgetting about us, or at least with the museums, it refreshed their recollection of what we do.

TM: Which dealers inspired you early on?

It is a curious thing. You might say that the British school as it then was a rather paradoxical place. Because on the one hand you might say it was outside of the mainstream. It wasn’t Paris, it wasn’t New York but there were some players there who had sophisticated taste and were demanding of the level of quality. In a sense they had to be because working out of London you had to be better than the other guys since you weren’t the first port of call for collectors. Paris even then was the touchdown place for many people. London did sometimes have the role of being a bridge particularly for Americans who would land there, feel comfortable and then head off for Paris. I would say, generally speaking, people from North America thought of Paris as a place to go and hunt down tribal art. In terms of people who influenced us I would say John Hewitt, Ralph Nash, and in the field of Oceanic and Polynesian Art, Hooper, Ken Webster, Oldman, and W.D. Webster. There was a whole tradition there which favored connoisseurship in the field of Polynesian Art which has always been a significant component of what we do.

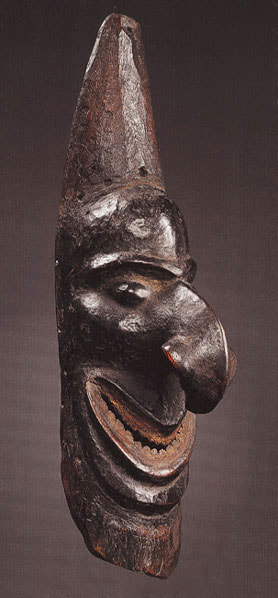

New Caledonian Kanak Mask

TM: You have a wide range of institutional clients. Can you discuss a few of the major high profile pieces you’ve sold?

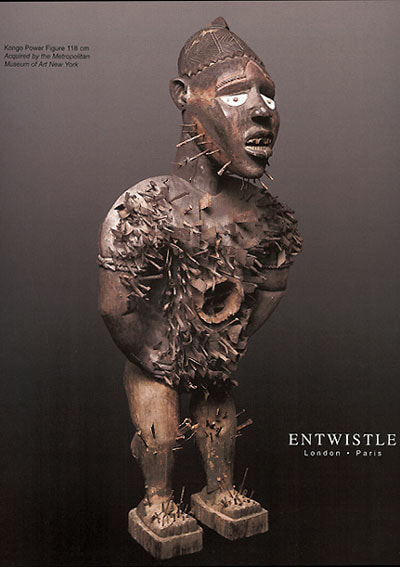

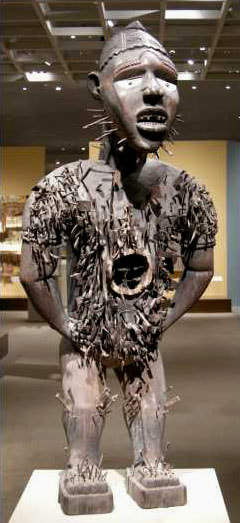

I would think we’ve worked with nearly all of the Tribal Art acquiring museum of North America of consequence. To a greater extent we’ve worked with the Dallas Museum of Art, a little bit with Houston, we’ve sold major pieces to Kimble Art Museum in Fort Worth, Chicago and a lot to the Metropolitan. I guess when you have a museum quality object you also have to consider what your best museum option is. We have a relationship with the Metropolitan going back more than 20 years. For example when Bobbie sold that unbelievable Congo Nail Fetish to the Met it had more kudos associated with it than it would have selling it to a much lesser institution. That very much is in line with reputation building as you’ve mentioned, to have a track record with the major institutions.

We’ve always made a point of that. But there is a cost assigned to selling to museums; it’s that you don’t get to sell the object again. It is gone forever more or less. Another museum we sold significantly to was Kansas where again Bobbie developed a very good relationship with Mark Wilson the director who proved to be more active with their acquisitions policy than the successive curators. They bought from us a great Benalulua female figure of the large scale type formally in the Tervuren, traded out of the Tervuren several years ago. They also bought a great Benin Royal collar head from the 16th century. Back to the Met, I had previously sold them a major double Madagascar post from the Epstein Collection.

TM: Was that Congo Nail Fetish the most expensive piece of the Tribal Art you’ve sold?

I think as far as I know that Congo Nail Fetish was the most expensive tribal art transaction in North America to date. It was over 6 million dollars. There will be other sales to come but for now I don’t think anything has been transacted for more. Many people came to us and said it wasn’t expensive, “You sold it too cheap”, but people will always tell you that.

|  |

Kongo Power Figure, Nkiski Nkondi (Mangaaka) ,118 cm

TM: Can you talk a little about the modern and contemporary paintings you’ve handled?

Well, let’s say the work we historically did in Tribal Art was always some form of trade. You could say that although I always thought of Tribal Art as “Art”, it was nevertheless and extension of antique dealing rather than art. I think things have changed a little bit; the way that younger dealers are presenting Tribal Art with thematic exhibitions, art fairs, catalogs, and websites is changing the way it is being dealt with and bringing it more in line with the way people deal with fine art as opposed to antiques.

Certainly that is something I find congenial. I much prefer this association. So when we began dealing with pictures we began in the same way as we were dealing Tribal Art. As traders we were either doing it opportunistically when we came across things when they were in collections associated with Tribal Art. In France we would go into a collection where somebody had been a collector of paintings and added some Tribal. We went to look at the Tribal, we then looked around and said there are some great paintings here lets have a go at those too. It was a way of extending our trading activities. I think I am a naturally curious person and I’ve had some art historical background in addition to my Oriental language studies.

So when I got involved in something I always wanted to research it and get to bottom of it. Consequently, when we started dealing in paintings in the 1980’s we started asking questions about them. I guess we’re dealing in classic modernism because that is what had the closest relationship for historic reasons, but what came before it? What happened in the 19th century and then in the 18th century?

Bobbie put on a fantastic historic show with an American Scholar named Ann Lowenthal of 16th and 17th century Northern Mannerism Paintings. It was a highly rated scholarly exhibition in our London Gallery. So, when we went into that business, I have to say we somewhat neglected tribal art in favor or fine art. I must say that we became a bit dissipated and overextended in our range. Looking back I think it was a mistake in strategy of being very eclectic and thinking the application of good taste and commercial good sense we could establish ourselves as dealers in a very broad range of paintings. I think that is a very problematical position in the incredibly competitive world we live in today. Within any given field there is too much competition for you to be a significant player unless you have specialist knowledge. We did it partly by getting partners in the fields where we didn’t have the knowledge but had the access, but even so it was a flawed policy. Certainly when we got in we found that dealing conditions by the early 1990’s were very tough indeed. What we had been doing was secondary market dealing, as I say analogous to the kind of dealing we were doing in tribal art. It was extremely tough, we were overextended, we were financed and our inventory wasn’t moving because nothing was moving.

So we had a space and we thought what should we do? So we said lets look at doing exhibitions of contemporary art which brought me into another phase which I found much more satisfactory. When I got seriously involved in contemporary art I was very stimulated by it. I was at that time somewhat bored by tribal art because I was kind of retreading old ground. The curious thing is that when you deal with contemporary art, even though you may not be dealing with a genius or somebody ever going to amount to anything, there is a certain excitement in discovering something in the studio that is completely new, is fresh, is alive and is part of your cultural ethos. You can talk to the artist asking what the intent is, what does he feel? There is a certain vibrancy there.

We get excited about the tribal objects but it is more about connoisseurship. The problem often is getting the same “high” that you got 10 or 20 years ago from something that may have been less good. You know we had the Rubenstein Fang head around 1983. That is probably one of the top two or three Fang Heads in the world. I’ve never had a Fang head as good since then. I’ve had some good ones but never one as good as that. I know realistically I’m not likely to get one either. So a fang head is out of the picture as far as a peak experience is concerned. You’re going to have nice experiences but you’re not going to be able to repeat that. Not because it is just not within anybody’s gift to do it, but the pieces are not there. That is an historic evolution in the marketplace where these things have increasing gone to very strong hands. Maybe it will reappear one day, we’ll see?

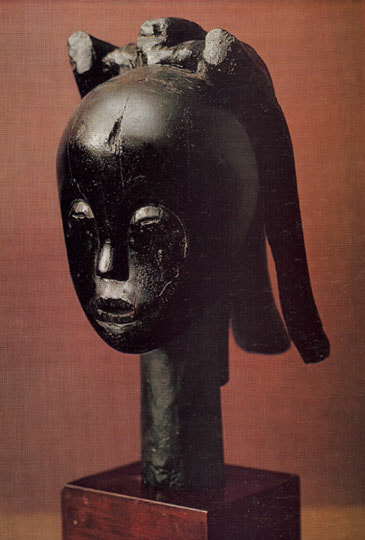

Fang Reliquary Head, Helena Rubenstein Collection, Lot 213 Park Bernet Galleries 1966

TM: How would you compare selling tribal art to selling paintings?

What do you enjoy more?To be honest you can’t compare because the contemporary art world or the fine art world, it’s not monolithic. It is spectrum of markets and one of the paradoxes is that when we became seriously involved in contemporary art we actually became beginners again. So we went down to the bottom of the totem pole and started to work with new artists. There was a huge disparity in what we were selling in tribal art which may have been $100,000 or $500,000 to selling things at unit value which may have been $5000, $10,000 and $15,000. In the early and mid 1990’s selling in the high-end was tough. It took awhile before the market really picked up and it didn’t really get going until the late 90’s and early 2000 when the market got really hot. Just now we’re going to see contemporary art being a bust. We don’t know how it is going to work but probably that low end market will be good; not to be good but viable. It is the nature of contemporary art that people like to buy, they like to discover, and it is very speculative. So you can buy an artist for $10,000 you think is good and might be worth a $100,000 in 5 years or million dollars in 10 years. That’s a fun game for people to play and also you can just take it out of your income, you’re not parking a lot of capital. So people continue to have an interest.

TM: Rumor has it that some Paris dealers were not initially happy so to see you open a gallery on 5 rue des Beaux-Arts?

It is certainly true that when we first went public with our presence on the rue des Beaux-Arts, going on five years now, we got some negative response. The dealers in question were honest enough to talk directly to us. It was a little bit ironic since one of these had always urged me to open a gallery in Paris on the basis that the more the merrier and that I would bring more clients to Paris. He said he was a little surprised it was on the same street as him! But I explained myself and I have always done a lot of business with this dealer and he recovered his composure and said very quickly “I think we’ll do a lot more business in the future.” And I think that Bobbie and I have benefited and been good to the Paris art scene because we have a very strategic approach. I think that is very often lacking as many Paris dealers operate on a hand-to-mouth basis, they’re shopkeepers.

I think being more strategic has been helpful. For example I consult very closely with people like Pierre Moos who owns Tribal Magazine and the Parcours. I’ve given him a lot of input and in turn he has been very good about canvassing the opinions of dealers and listening to what their input is. So I think ironically we’ve been very beneficial to the Paris art scene. Actually there was one other dealer who had a passing reaction. I think what they didn’t like was the surprise! The fact of the matter is that when you’re going to do something like this you have to surprise people because if you telegraph your plans ahead of time you can be sure someone is going to put a spoke in the wheel. We didn’t want any competitive bidder for the premises that we had in mind or anything like that. In the beginning there was some surprise and alarm but its proved to be unfounded.

New Ireland Malagan Mask

TM: What kinds of objects are most suited to the Parisian market as opposed to the American market?

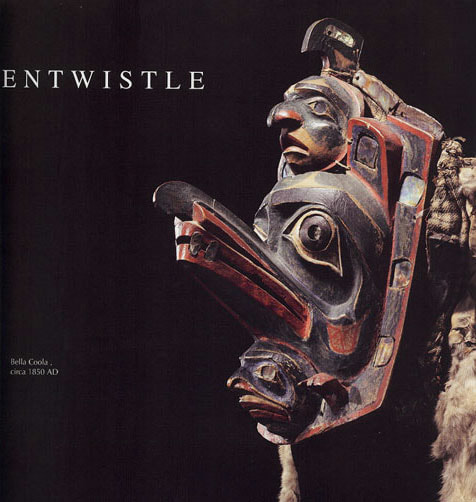

Pause… Well, the first thing I would say is that the American Buyer is still a very very significant component of the market, particularly when it comes to the high-end. Even when the dollar has been weak, as it is now, the American buyers have been very active and at least for us have been important. There have been special situations in France like some of the star pieces in the Verite collection were things of historic interest. Like certain pieces the Quai Branly has acquired that have French associations. You might say the French are possessive and protective of these things, so they have outbid the competition of certain buyers. People that otherwise would never be players have come forward in the market. For example, in the Verite sale of the great Fang Ngil mask to a French woman was a sale that wouldn’t have happened in my view if this had come from an American collection and been sold in a New York auction. I wouldn’t say it was protectionism exactly but a certain interest in something that was perceived to be “French”. We’ve seen that with a Northwest Coast Mask that we bought in a provincial auction that came from Lady Straus. It was then pre-empted by the French state and is now in the Quai Branly.

It is hard to say there is any real taste differentiation possible. I think taste like everything has have become more globalized. You might say more homogenized. So that is a difficult question to answer.

Interior Entwistle Gallery, Parcours des Mondes 2005

TM: What art fairs do you currently participate in and which seem to be the most successful?

Since we’ve participated in the Parcours, business has been very good for us. It’s a paradox in a way because you might say participating in an art fair in your home patch is a bit pointless but it gives you the ability to follow up leads and be available and accessible to people. A lot of people come to Paris for the Parcours. The same people will come to Paris for other reasons. They may come for vacation or they may come to look at tribal art at other times. So I think that if you were a dealer from Rotterdam, if you don’t make good sales during the life of the Parcours, the knock on benefit is much less than if you’re a Parisian dealer who has the same results. We’ve never had a bad one, we’ve sold well at every single Parcours but we’ve also had a longer term benefit. But even for French people, there are people we don’t know that come into the gallery at the Parcours and come back into the gallery later in the year. To give you an idea just how insular it can be, there are many people in France, and it may sound a bit conceited, that have never heard of us. So they say “well who are these people, we don’t know them.” They live in a bubble and always deal with the same Parisian dealer they know. They’ve never been outside that don’t know there is a wider world out there.

Paris Parcours 2008 We just did our 3rd Biennale. We skipped one because it used to be held in a very depressing venue, the Carousel de Louvre, which is subterranean and a terrible place to be 10 days 12 hours a day. But since they’ve gone back to the Grand Palais we’ve felt very much like being part of it. Our most important piece was a Cameroon Fang followed by some 18th century Maori panels from Sarah Bernhardt. The price points on both of those things were very high and certainly there was resistance at this fair. Initially we had interest for some of the very expensive items. Typically in an art fair context those expensive items don’t walk out of the booth; you have to develop those sales during the fair and beyond. In this case “Black Monday” intervened (September 29th 2008) and suddenly the whole atmosphere changed and that derailed those very expensive ongoing conversations. Even though, this year at least, it was not the easiest place to sell, because it is local to the gallery and because it has a tremendous prestige with the French public, it is an absolutely must do fair for us.

Being Parisian dealers, we have to have the “prestige” associated with being there in order to keep the prestige of the gallery up. It was a difficult fair this year (September 2008) although we did quite a lot of referral business where most people didn’t want to pay the price point we were offering at the fair. However, they went back to the gallery and made purchases there. Also preemptively people bought things that we were going to put at the fair before they went to the fair, so it cuts both ways.

The third fair we’re doing for the first time and we’ve been very anxious, is Maastricht. We’ve been invited and now have an opportunity. It is a very thin field there. Tribal Art has been well represented by Bernard DeGrunne who I think for strategic reasons were keen to help increase the tribal presence there. He has always said “please apply, please try to get in”. I think in a fair where there is a venue having no natural public you need a certain momentum, some force or gravity to bring people in. Anthony Meyer is also in this fair and is an incredible presence in this field.

TM: I hear the vetting is incredibly tough there, sometimes unreasonably so.

It still doesn’t stop a few odd things from slipping through…

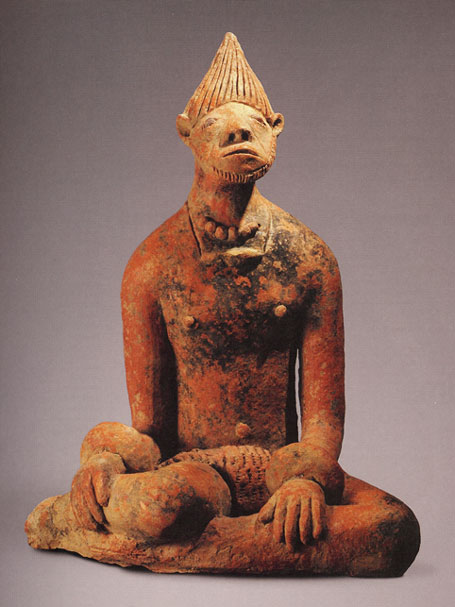

Djenne figure

TM: If there were no shortage of great material from one culture or region (African, Oceania, N. America) what would you prefer to specialize in?

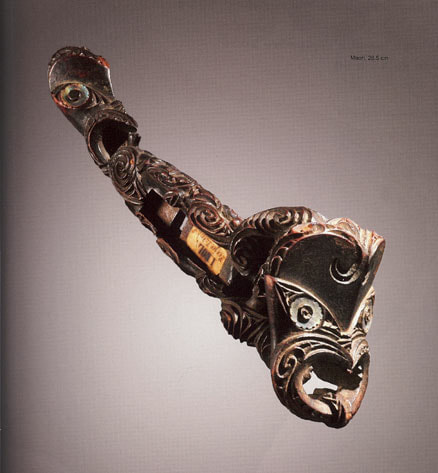

I would be reluctant and saddened if I had to omit one of those areas, although there are some exceptions. Overall I’m more excited by Polynesian Art than Melanesian Art but there are some extraordinary pieces within that realm. It is invidious to try to make preferences. Would I be more excited to have a great Hawaiian figure, which is dreaming the impossible dream, than to have a great Yuat figure like the one in the Friede collection or the Beyeler foundation? I guess the Hawaiian figure would carry the day for me. I suppose in terms of Native American I could most easily give up the Northwest I guess, partly because one doesn’t get enough opportunities, so what would I be giving up really? If there was an equal flow of material then it would be a tougher call.

TM: Do consignments work best with your business model which involves selling very expensive pieces?

Yes, I would say that consignment today has become an essential part of dealing at the high-end of the market because people, quite reasonably want to extract as much of the full market value of what they are selling as possible. I think there are two ways to do it. One is to give it to a dealer who has the confidence of his clients and is able to command high prices. Our business depends significantly on confidence. The other is to do it on terms that are as favorable as possible. I’m mean the dealer has to make a living, but the consignor also has to look after his interests. Clearly if you insist on selling to a dealer, because a dealer has to make a return on capitol, you’re going to get a much lower percentage of the retail value of you’re object than if you consign it. So we’ve found that, rather ironically, a lot of owners prefer to consign rather than to sell because it reassures them that they’re getting a better “shake”.

If a dealer walks in and says “yeah I’ll give you $100,000 for that”, they know damn well he’s not going to sell it for $120,000. He’ll have to sell it for $150,000 or more. As every dealer knows there are no sure bets. You can think that a thing will sell tomorrow but you can be wrong. I’ve been there and frankly people who’ve spent a lot of money on inventory in September can quickly find that in October it is a very different picture. I think we’re going to be seeing significant discounts on estimating auction values and private sales over the next 12 to 24 months. There is no question about it in my mind.

I think for the dealers the challenge is to continue to trade and to protect their margins. Where you have a problem is with your old inventory. Even if you can sell your old inventory and reinvest at lower levels, protecting your margins on resale you can still have a viable business. The worst scenario is that dealers will have to contend with is a “stuck market” which can easily happen. Although you as a dealer maybe prepared to buy at a lower level, or to take on consignment at a lower level, private sellers are going to say, “Ah I don’t need the money now, the market is going to come back in two or three years, I’ll wait and not sell.” That’s what we’re going to see, especially in paintings, big time.

PART 2

Lega ivory figure (iginga), 16.5 cm 18th century

TM: You and Bobbie have turned up some fresh discovers apparently by searching out the relatives and family members from famous voyages and expeditions? Has that type of genealogical research paid dividends for you?

The first genealogical research we did was related to the Benin Expedition. This was something I used to do before I was with Bobbie. At the time I really knew nothing about running a business and this was born out of my incredible naivety. I was really an academic and what interested me was reading books, so I naturally thought I could do everything through analysis and research. So I would go to a library, but that was not a very dynamic business plan. We had some successes and traced some surviving descendants of the exhibition participants and bought some material from them. We also located some material that was not available. It was successful relative to our career levels at the time which were the early days. But it was certainly not a viable business model and I would never dream of doing it today. If I had gone to African with a few empty sacks and gone into Nigeria the way Jacques Kercache did or Philippe Guimoit did, that would have been a more viable plan. That said, I enjoyed the treasure hunt aspect of it. I enjoyed crunching the data as it were, and the sleuthing aspect of it. This still occasionally comes into play but it tends to be more now with tracking down provenances and finding out early histories of things.

TM: Can you recall an especially interesting story which involved a great find?

I can tell you a modestly amusing one which involved Bobbie and my in-laws on a trip to Scotland. Bobbie said look, “this is the deal, no antique shops. We’re not going to ruin my father and mothers experience by stopping at every antique shop we pass”. So I reluctantly agreed to that deal. We were looking for a traditional Scottish Tea Shop with scones. I dropped everyone off and went to park the car. I passed an antique shop and saw a spear in the window. After the Tea Shop I said more or less on bended knee, please I saw a spear in that shop can I go ask them if they have anything else? The shop owner was having a long conversation with someone. This was awkward because I needed to get back and didn’t want to screw things up with the in-laws. I eventually interrupted him and said, I see you have a spear in the window. Do you have any other African things? He said “What, you mean like Benin Bronzes for example?” I said, “yeah right like Benin Bronzes.” He said, “Yes, Just wait while I finish with this customer“. At that point I would have waited all night to see it! He had a Benin Bronze figure but it was in the bank vault, so I later made an appointment to see it. He flew to London to show me and it turned out it was a rather fabulous piece. To cut a long story short we bought the piece from him and it ended up in The Met. That was the one and only antique shop we went into during the whole trip. That was kind of serendipity.

I have another story but I can’t talk about it because we have not gotten to the end of it. This story which I give a fifty-fifty chance has been going on for 25 years. It involved some genealogical research and other research with some amazing coincidences and funny twists and turns. Right now I can’t discuss it because it is in play.

TM: I understand you have a massive library of books at your London gallery spanning floor to ceiling?

Yes, the books are under the eves of a rooftop and the shelves run about 15 feet high. The building was built in 1890-1910 as an art dealing concern. It was obviously a very grand affair at the time. I don’t actually know who the original occupants were, I should find that out. The showroom is setup as a library where we show art but we actually focus our inventory in Paris. The environment of books is a very good environment for selling because it is knowledge. Knowledge in our business is security. Buyers, with good reason in my opinion are cautious since this field is fraught with authenticity problems. Buyers are reassured by knowledge.By the way going back to your question about reputation and mystique, one of the things we always provided, particularly in the early days, was very extensive write ups and documentation to our clients. One of my colleagues Alain de Monbrison, bitterly reproached me. He said “It is just terrible what you’ve done; now we all have to do it”. We did become a little bit lazy about it but now we have a fulltime researcher and archivist which serve us well.

TM: You knew many of the great collectors like George Ortiz, Douglas Newton and others. How much knowledge has been lost and can it ever be recovered?

I think I can say to collectors without being unfair to them, that many are not fulltime collectors but dealers are fulltime dealers. The greatest repository of knowledge, generally speaking, is held by the dealers. Sadly very few dealers are also scholars. It is in the nature of it, they don’t have the time, and you can’t be a businessman and a scholar at the same time. You can be a “well informed” dealer, a professional with good connoisseurship, a great eye and great knowledge but not be a great scholar and recorder of the information you have. Consequently, I think the greatest loss to the business is the loss of dealer knowledge. The one saving grace is that particularly like in a city like Paris, where there is a certain “milieu” where these events take place, knowledge is shared. There is a passage of knowledge from older to younger.

I think one of the great benefits that any beginning dealer has in Paris is that they can very quickly acquire knowledge. Whereas, I think in the states it is much more dispersed. I think in California you do have some good people and some people who share knowledge but it is not as intense; they don’t sit around the cafe sharing information the way you have in Paris. They don’t meet on the doorstep of Drouot and discuss the finer points of Fiji Clubs. So you have a culture of connoisseurship in France where there is some transmission of this information but a huge amount gets lost. I think another point is that, whereas we once sold the Rubinstein Fang Head and are unlikely to ever sell it again; many younger dealers will not have the opportunity. That’s just for purely logistical reasons, not because they are not talented or dynamic but the material is just not there to be handled. That is a disadvantage.

TM: Do you see fewer generations of art dealers emerging? As great material gets more scarce and costly, couldn’t our business be in danger of dying off?

Well certainly some aspects or some fields of the art business have historically gone extinct, or relatively so, by virtue of the lack of material. I mean if material all ends up in institutions it’s no longer available to deal. The possibility of creating excitement and interest among the collecting community diminishes. It is not because there is not enough for the dealers to work with but it is because there is not enough for the collectors to buy. If you have an active collecting community then there will be dealers to service it. A field on the decline would be the case with medieval art. It has been attenuated with very few dealers because there are so few pieces and overall the connoisseurship of collectors needed to support is diminished. Certainly if there were more material the field it would be more viable.

I don’t presently see that as being a problem in Tribal Art. I think what we’re going to see, or what we are seeing is a higher rate of rotation. We’ve seen that in the picture (painting) field. It is going to slow down in the next two years as sellers become more skittish because of uncertain (sale) results. They’ll say, “let’s get out- get out!” It is proverbial that high prices bring material to the market, so material has been coming up particularly from discretionary sellers as opposed to estates.

I think unfortunately we’ll see a generational shift here where certain collectors and their collections are going to come to the market. Its a bit sad since many of these people are my friends and have been my clients for years. There is a whole generation of collectors who came on strong in the 70’s and early 80’s who are now quite elderly. Some of their collections, like the Rosenthal sale at Sotheby’s for example, will come up to stimulate interest and renew the market. Even if prices are depressed, that can be good because it can result in greater distribution which isn’t a bad thing. I used to be pessimistic about the future, but I’ve seen there are people like you who are enterprising and finding new ways to deal will always make it. So I’m fairly sanguine on it. I also know very well that there is nothing more replaceable than a dealer. I could retire, disappear, whatever… and the market would not miss a heartbeat. That is just the way it is. Its “tough titty” but we are completely dispensable to the operation of the market. I’ve seen the good and the great disappear progressively over the years. It doesn’t make a dime of difference.

TM: What advice would you give to new collectors entering the market?

There is one bit of advice that nobody wants to hear which is do your homework. I say that both to help encourage new collectors to look after their own interest and also from a self-interested point of view, because I think that responsible honest dealers benefit from having informed clients. The old adage, “the best client is an educated client”; it’s true if you’re selling good stuff. There is a MASSIVE kind of “hinterland” in dealing in the most appalling kind of fakery. Even in France where we’ve said there is this level connoisseurship, there are auctions almost on a daily basis in different provincial centers. You see the “La Gazette Drouot” they sell rafts of stuff and just churn it basically. They take it to Reims, offer 200 lots, 20 of them sell then they take it down to Cannes, sell a bit and add 20 lots… It’s an absolutely appalling system and the same thing is happening on eBay. It’s very unfortunate, but in a sense collectors get the collection they deserve. So if they want to deceive themselves, well that’s their choice.

TM: Although you sell at the top level, isn’t it also important for there to be a healthy middle market for the longevity of this business?

I think where I always see a problem is the definition of the “middle market”. Does the middle market refer to a “price point” or to a level of “quality”? Because you can have a minor piece, take a Bembe figurine where you could have a price spread of between $3,000 and $120,000. Now, some people would say well what is the middle market? Is it $60,000 or maybe $120,000 is the middle market; it might be the top of the market? That would be the supreme example. But if you took the spectrum represented by that particular category of objects and took the middle point, the mean, you’re always going to have a problematical area. What you’re talking about is something that is in the middle range of quality for what it is and costing quite a lot of money.

In my view you can not make it a price point. You have to make it a quality spectrum. The small collector can get their hands on the 2’s, 3’s and 4’s because they are not expensive and easier to assess on a quality basis. When you get to the middle range, the 5’s and 6’s in the quality spectrum then it becomes more difficult because people are being asked to pay plenty of money for something that isn’t great. At that point the small collector can’t afford it and the big collector says, “Are you telling me this is a 6? I only want an 8 plus so I would rather wait and pay $120,000 for my Bembe than get a so-so example.” So if the middle market is defined as a price point the question is a little meaningless, but if it is defined in quality terms then the middle market is always a problem. The middle market always gets hurt and would be hurt now.

TM: After steady appreciation over the past years, what do you see happening to the market for tribal art in the next 3 to 5 years?

I’m pretty optimistic. I do think there are grounds for caution because the American market, which has always been an engine in the art market, has not developed so much in terms of younger collectors. I’m starting to see some now, but in a slightly different pattern than emerged in the 70’s and 80’s where you had a very broad base. Today you have a got a certain number of strong players. Some at the top of the market and some near the top that is active and able to support a significant part of the market. I think you have a different kind of player now. The professional class like Doctors, Psychiatrists, etc, has a tough time competing on prices anymore. So you’re looking to people who have much more significant means but consequently become bigger players since they can buy more and more often. It is not a secret I worked with Bill Ziff. He had an appetite to buy not only some terrific things but to buy them in depth. He bought many things in a way most collectors were not able to do, so we had a major player. In Klejman’s early days you had a similar phenomenon. In the 1960’s there were fewer players but there were meaningful ones like Jay Leff, Rockefeller, and the De Menil who could spend a great deal of money and buy frequently. After that it became more democratized and broader based. I think it has shrunk again where you have many smaller players. I think the middle market is probably weak today.

Tribalmania extends its sincere gratitude and appreciation to Lance for offering his insightful and timely views!