Interview conducted and written by Michael Auliso and republished here with his permission.

James W. Willis

27 September 1934 – 2 September 2019

TM: How did you begin selling Tribal Art?

WILLIS: I started in 1972, it was unplanned. I had kind of a rough, but interesting job as a book binder. A friend said she had a commercial space available for rent in Sausalito above Swenson’s ice cream parlor for $65 a month. She asked, “Do you know anybody who might want to rent it?” I said, Yes…. I do! I had no idea what I was going to do but I knew I didn’t want to do book binding anymore. It was interesting but didn’t pay very well and it was arduous. I had been a ceramist, so thought I’ll open a ceramic store. Then I thought about it, in the history of the world has a ceramic store ever made a profit? My conclusion was it probably had not. So, I decided, since I had been collecting African art, I’ll become an African and Contemporary Art dealer.

My model was the David Stewart Gallery in Los Angeles that showed African and contemporary art. Incidentally, I bought one of my first pieces, a Chi Wara from that gallery in 1955. At $65 a month I didn’t think my risk was too high, and I had no employees. My first exhibition was of a contemporary painter named Peter Kitchel, who has actually become a well known print maker. I also included a few African pieces from my collection. I mainly made my living from African beads. I would restring them and if I sold a couple of strands a day I made my rent and food. That is how I started, I didn’t really plan it, it was just extemporaneous.

I was a contemporary dealer as well as a tribal dealer for the first ten years. I stopped doing contemporary are because I had the realization that if I tried to do both, I would be mediocre at both. They are really very different professions. Being a tribal art dealer you’re always searching for objects, while in contemporary art you serve a “mothering” function; the artist wants you to be around all the time. When you can find good tribal prices you need to be quick to move. I felt that many others could be contemporary dealers and I decided I wanted to be a significant tribal dealer. When I say “Tribal” I specialize in African, Oceanic, and Tribal Indonesian with a little bit of Nepalese and Tibetan art.

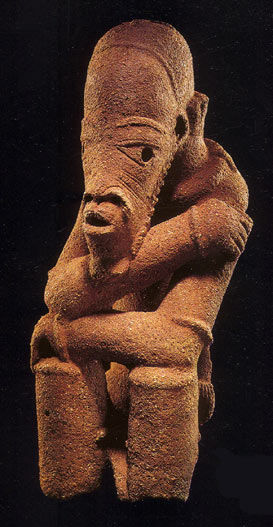

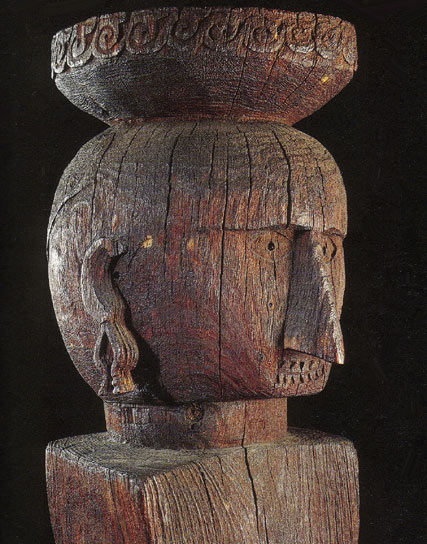

Igbo Chief’s Figure, 19th c., 54 inches

TM: How do you feel the business has changed since you first started?

WILLIS: Well, 34 years is not a long time but in this particular area it seems an eternity. When I first started there was a lot of material coming out of the field. There were whole areas of African Art that were unknown, things we had never seen before. I remember buying a couple of Moba pieces and then never saw another one for 20 years. Overall, there was more material around, prices were lower, and one could go to Africa and find authentic material with some regularity.

There were very experienced people such as William Fagg and others who were great sources of information. Their experience and knowledge is irreplaceable. The books are better now, but the ability to talk to these important people who have left us is a big change. Obviously prices have gone way up.

In a business where sometimes the rewards can be substantial, keeping ones perspective and realizing at the end of the day honesty and consideration for your clients who allow you to be in this business should be foremost in your mind. As prices go up, temptations will go up also….. keeping a moral compass in this shifting economic situation is critical. As the scarcity of material increases, the number of dubious pieces that are appearing is something that we are all going to have to deal with. That is the biggest threat to our business. Collectors have to be intelligent and careful. Dealers have to be very intelligent and careful. I think the problem with fakes and tourist pieces sold as real pieces has always been great, but as there are fewer genuine pieces, I believe it has become more important to dwell on problems of authenticity. That leads into the question of provenance which is a very existential question.

In some ways the business hasn’t changed at all. On the whole, the people who collect are the ones who are passionate about it. There are fewer public galleries in America and that is a big issue. It is becoming a business of private dealers with the exception of Europe where there are lots of galleries.

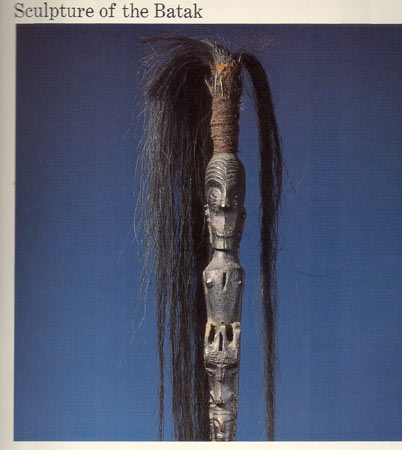

Nias Royal Figure, 30″

TM: What are your thoughts on the issue of provenance?

WILLIS: I’ve been thinking about this a lot and I think it is a question of definition. When clients ask for provenance, I think they are asking for something else. When asked for provenance we say, I bought this from so and so or this was published in an auction catalogue or some other history of acquisition. In other words, historical information which is not all that meaningful. I think what people are really asking for is some kind of documented assurance that the object is real and just giving them the history of who owned the piece doesn’t satisfy that, in my judgment. I’ve been contending with this and I realized I’ve been doing it in the wrong way because I’ve been trying to just answer the question of pure history without answering the real question which is, “What assurance is there that it is authentic and of high quality”.

Provenance in itself is a strange thing. I’ll give an example, I bought pieces in Paris in the 1950’s and did not have the concept of fakes. I did not even know what African fakes were and since I had so little money I bought from the worst and cheapest dealers. I recognized after I started my gallery that the majority of these pieces I bought in the mid 1950’s were fakes. So by telling somebody that something was purchased in the 50’s doesn’t really give them assurance. There were also many fakes in collections in the old days. So, what does provenance really tell you? I almost think we need to redefine the word, because I spend all this time giving people the “history” which doesn’t guarantee authenticity. I can point out many Senufo fakes which were made for European tastes in the 1930’s. I see them all the time. If I vet one out of a show people might say, well how can this be bad, it was published in 1939. Well in 1939 the Africans were making fakes. So this becomes a very complicated issue and I think we are asking the wrong question and giving people the wrong definition. I’ve just begun to think about this because we give people what they ask for, pure provenance, but at the end of the day it tells you “something” but not very much.

Nok Terra Cotta Nigeria, Age 2000 yrs

TM: I think most people perceive you as an African Dealer. Do you find that selling other types of art such as Oceanic and Indonesian to be more challenging?

WILLIS: No, I think the reason I sell more African art or deal with it is that there is just more of it. I mean Africa is a huge place. This is one of their great sculptural traditions. For instance, most of the Oceanic islands are relatively small. It is just that there is more African material. I’m not saying it is better, just more abundant.

I have no reason to rate one culture above another, and in fact it seems the market and demand for South Pacific is greater, while I think the supply is fairly small. I don’t know if John Friede’s installation at the DeYoung Museum is accountable for that. I like all categories pretty much equally and at one time I was very active with Indonesian art, particularly Batak.

New Guinea Yangoru figure

TM: What is the greatest collection you’ve purchased?

WILLIS: I purchased a collection of Batak material from Sumatra and published a catalogue called “Sculpture of the Batak” with Mort Dimondstein. We bought the collection together during the seventies at 18 percent interest rate, and nobody liked the pieces for about two years. In the end I learned a lot about Indonesian art. We did fine eventually, but I remember that 18 percent was really clicking along.

Images take from “Sculpture of the Batak” Exhibition Catalog May 15- June 30 1979

TM: You’ve appraised many important collections. Does one collection stand out for its uncompromising quality?

WILLIS: That is a really tough question. I was hired by the Disney Corp. to annotate, appraise, and negotiate the purchase of the “Tishman Collection of African Art”. This collection had a lot of great pieces in it, but I think it was also known that it had a lot of pieces that were not so good. I would say this is probably the biggest and best known collection I have done. I’ve also appraised significant Indonesian collections like the Fred and Rita Richmond Collection, which is now at the Metropolitan Museum . I was involved in the sale of the Helen Kuhn collection to George Hecksher, who is promising the collection to the De Young Museum, I believe. I do a lot of IRS appraisals for donation. I’ve done a few appraisals confidentially that are significant but I am not free to say what they are.

TM: Have any of your appraisals been particularly difficult relative to others?

WILLIS: I think the most disheartening appraisals are collections of bad pieces. I’ve appraised collections where virtually every piece was a tourist piece or a fake and there is nothing enjoyable about that. It is uncomfortable to be hired by someone to give them nothing but bad news.

I also do evaluations for people who feel they have been defrauded. I’m one of the few dealers who will do them. I feel strongly that the collectors deserve assistance when they believe they have been defrauded. If the collectors do not have anyone to go to, it may seem that the dealers are participating in a conspiracy. So I reluctantly do this kind of work because I feel that someone should do it, otherwise the collectors are really left with nowhere to go when they feel, either rightly or wrongly, that what they bought isn’t what it is supposed to be. These situations can be very difficult because you obviously anger the sellers who either knew what they were doing or in many cases did not. Often they don’t accept your verdict and sometimes they can get hostile. You just have to live your life ethically and call it the way you see. It is your professional opinion and that is all it is.

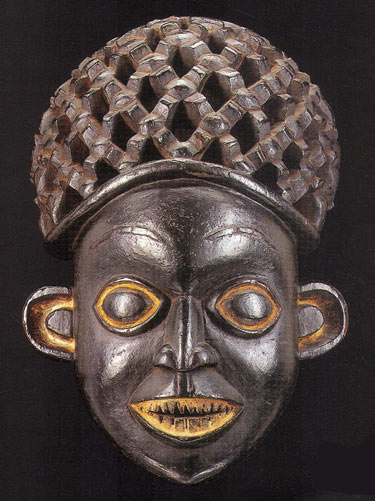

Bamun Mask Cameroon

TM: You closed your retail gallery on Geary Street in 2001. Do you ever miss it?

WILLIS: It was probably the right decision based on the scarcity of material. I do miss it because what I really loved doing was putting on “special exhibitions”. The trouble is that this is very difficult to do now. Over my career I’ve had a lot of exhibitions. I had a Gabon exhibition with fourteen Kotas and a few Fangs in it. It is just not possible to do that with any regularity now and so I felt I was reduced to “theme shows”, whereas I like to try and do shows that have never been done before. To my knowledge when I started in 1972, I was the first dealer to do this as a gallery. Most dealers ran their places more like shops. I’ve always liked to have exhibitions, I just found that increasingly difficult.

I was talking to Daniel Hourde in Paris about the Fang show they recently put on and he said that he and Philippe Ratton worked on that for 5 or 6 years. To have those kind of resources in San Francisco , is very difficult. I think the French and Belgium dealers who are putting on these significant shows deserve a lot of credit. Lin and I went all the way to Shanghai to see a Congo show that Mark Felix curated. These are big efforts and I think the exhibitions are quite remarkable.

TM: If you could have just one object back that you previously sold, do you know which it would be?

WILLIS: (laughing) Yes. I saw it just the other day. I believe it to be Zulu, a small figure which is on exhibit at the Met belonging to Udo Hortsmann. For some reason inexplicable to me they call it Makonde and it is located in the East African section. It is a great figure which I sold years ago to Udo. I didn’t give it away but I think I would love to have that piece back. I do not regret selling any object. I price pieces at what they are worth. I’m delighted when an object becomes worth a great deal more than I sold it for, and the client prospered. Of all the pieces I can think about, that is the piece I would love to have sitting in my living room right now. It is sensational.

TM: At 72 you seem to be at the top of your game?

WILLIS: I think one of the nice things about being an art dealer is that one becomes stronger with greater experience. I can not work as hard as I used to, but my memory is still good; it is not a profession that you need to retire from when you are past 65. I still have good energy. I think an enormous amount of experience has got to be an advantage, and if you’re honest with people over the years, that gets around and I think that is the most important thing that you have. You tell the truth, you don’t make stuff up and you do your best not to make any serious mistakes.

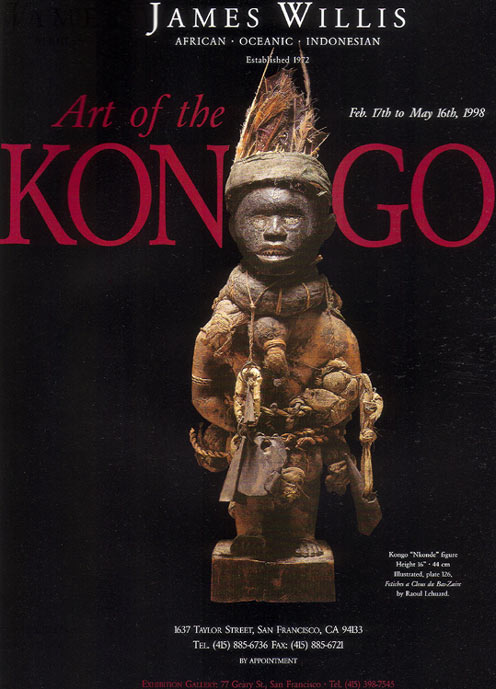

Yombe Mirror Fetish, Congo. Ex. Mangio Collection, Published “Art Bakongo” by Lehuard Vol. 2 Plate 714

TM: What inspires you to keep working and offering great pieces for sale as opposed to sitting on a beach somewhere?

WILLIS: I love the material, I love finding the pieces, and I love finding somebody who agrees with me. If I was a roofer, I would be sitting on a beach. This activity still interests me and I see no reason to quit, plus I have such a large inventory (laughs) that I have to figure how to keep moving. Basically I enjoy it. It is like any job, an enormous amount of it is like house work. Sometimes we’re more like warehousemen than we are dealers. Any dealer that has experience will tell you that he spends more time cleaning up and moving things around than doing anything else. I don’t love all of that, but I still do it. There is always that ‘great piece’ out there that you are going to find. I basically like the people. I like the dealers. Most of my clients become my friends. People who collect tribal art have passion, so it provides me an interesting and wide ranging social life.

TM: You’ve conquered a series of health crises, what do you attribute your amazing resilience to?

WILLIS: I think part of this is genetics. My mother and her twin sister are 94. My mother’s sister’s son is Senator John McCain from Arizona , and we all know how tough he is. I think I got some genetic help, biology, luck, and good medicine. I had a deadly cancer once and at the time I was the only known survivor. I had a pretty bad heart attack too. I’m clean living, I exercise a lot, I don’t drink much and have never been over weight. I think that all helps but most of it is just genetics. And perhaps one of these African fetishes has helped.

Bamana Door Lock, Ex. Stanoff collection

TM: You used to field collect. Do you occasionally still do so?

WILLIS: Field collecting is a kind of a misnomer. Nobody field collects much. You go to the field, which means you go to the country and you buy the best pieces from the best dealers. The number of the pieces I’ve truly “field collected” are low. I think I bought a Senufo stool that a woman was sitting on. The time it would take to trek around to small villages and negotiate purchases is just not economical. It is always the same, there is a hierarchy of dealers and the best ones have the best pieces and are usually in the big cities.

No one can know the number of pieces still in Africa . Obviously, there are pieces the people are keeping. There are still pieces in the ground. However, I would not consider going to Africa purely on a collecting trip. There is limited collecting in Mali, because we have an agreement with Mali that significant things can not be exported, In addition, I am on the Cultural Properties Advisory Committee which is by Presidential appointment. So obviously I will not be doing any collecting in Mali . In Africa there may still be masterpieces but they are only there because they are not for sale.

TM: What advice would you give to new collectors just starting out?

WILLIS: That is a complicated question. Let me turn that around. I have a much easier time placing an object with a person who is knowledgeable. I find it difficult if someone doesn’t know anything. If they don’t know the difference between a $500 piece and a $50,000 piece, how are they going to make choices? So it seems incumbent upon a collector to acquire some experience. Books help, as well as seeing as many objects and exhibitions as possible. This is a very small world and it is not extraordinarily difficult to find out who you should be dealing with, and perhaps who you should avoid. It amazes me that someone who will research everything about their business, will buy an expensive object without considering the integrity of the dealer or learning about the material.

Tanimbar Post Figure, Collected 1900 by Van Oldenbarnevelt

TM: It seems that more pieces and collections are going to auction these days and there is a preference for collectors to overpay at auction as opposed to buying from private dealers. Do you feel the days could be numbered for dealers or will we always serve a function?

WILLIS: I don’t think our days are numbered at all. I think we support each other, and we can not exist without the other. I think it is important to have a public auction forum so people can see that the objects sell for a certain price and that the objects have a value. While auctions do have an educating function, collectors need to spend a lot of time with dealers and their inventory, looking at and discussing the art, learning, getting advice, etc.; auction houses do not provide that in the same way. Some objects do well at auction and some do not. I see auctions as complimentary and have never felt they are the enemy. We are seeing some very high prices at auctions. I can not be sure of the reason. I suppose people feel more secure when someone else is willing to bid nearly what they are willing to bid. This doesn’t happen in a private sale. One of the reasons some people buy at auction is that it does not take as much effort as going around from dealer to dealer.

TM: What are your thoughts about the prices realized at the Verite sale in Pairs June 2006?

WILLIS: Time will tell if these prices are sustained, and if these were rational prices. If they are not sustained and if the same pieces reappear at auction a year from now and sell for much less, then we can conclude that the prices were too high. I think this was a specialized auction which was brilliantly promoted. It happened at a spectacular time, coinciding with the opening of the Quai Branly Museum in Paris . I suspect some of the buyers were not terribly experienced and wanted to buy a piece in that auction at that time. Again this is all speculation and we will see if the next two or three years bring the same spectacular results with the same kind of material. Only then can we say they are ‘just’ prices. If the market drops substantially or reverts to what it has been, then it was a one time occurrence.

TM: What do you see happening to the market for Tribal Art in the next 5 to 10 years?

WILLIS: I know more about the past. I can only speculate about the future. It is a great art. It has got that. I loosely quote Picasso toward the end of his years, “The greatest artists that ever lived were the Africans.” I have a tendency to go along with that. When something is of great quality, it will maintain its value. What we will have are some ups and downs. All art depends upon certain economic factors, and is bought with discretionary funds. If there are bad economic times or we have a decline in the housing market, I could see the market for all art softening. African Art is still relatively inexpensive compared to other great art; witness a 125 million dollars for a Gustave Klimpt. Klimpt is a fine artist but he is not Michaelangelo, de Vinci or Rebrandt. So, the prices we are seeing in African Art, which are in the thousands, with some exceptions, do not have very far to fall. But if tastes change in the future and people want something else in their lives, then who knows what might happen. The thing is that prices have never fallen much and there is a good economic reason for that. This is a non leveraged market. The securities market is often leveraged; the housing market is leveraged, but people who own tribal art have paid for it in a relatively short period of time. So we do not have the problem of an enormous amount of material hitting the market. In fact, when prices go down, the material becomes scarcer as people simply keep their objects.

Songye Magical figure, Collected by Dr. L. Van Hoorde in 1934Published in “Songye: Masks and Figure Sculpture” plate 99

TM: What do you do to relax?

WILLIS: I like salt water and fresh water fly fishing, but that is pretty active and hard work. I went fishing in Christmas Island and Tierra Del Fuego recently. I love to travel. My ideal would be to do less busy work and more traveling. Lin and I generally spend a month in Asia each year. We try to go to Africa every two years, we’re in Europe two or three times a year… I exercise. I like to read. I’ve got four children so I have some responsibility there. When one thinks of one’s ideal life, I don’t think I’m too far away from it. I live in a city l like. I have a profession I like. I have a wife whom I love. One can always improve ones life, but I feel pretty lucky. I would like to take up a new competitive sport (laughs), because the ones I used to play, are too hard on my body.

TM: What are you’re plans going forward?

WILLIS: We do the San Francisco Fall Antique show, and our SF Tribal group has our annual show. In February I’m doing the Caskey Lees San Francisco Tribal Art Show. I contemplate whether I should spend more time in Europe because the center of the tribal art world is definitely Paris now. It is logical that it would be, the auctions are there, and the French were the first people to really appreciate Tribal Art as art and not as ethnology. I find the whole environment in France in terms of the art scene, the people, their sophistication, and aesthetics to be very admirable.

Michael Auliso with Jim and Lin Willis 2005 The Yombe Figure was published in 1923 in a Paris Exhibition Catalog.

Tribalmania extends its sincere gratitude and appreciation to Jim Willis for offering his insightful views. Michael Auliso

Lin Willis:

Dearest Friends, I want to thank you very much for reaching out to me with your kind words, condolences and memories of Jim. I am deeply touched. For friends learning this sad news now, we shall all hold special memories.

I can only add that I am incredibly fortunate to have Jim in my life. He was unique, a bon vivant full of life, curiosity, and engaging the world. We had deepest love for each other. We enjoyed being together 24/7, working as partners, traveling, he taught me so much, including the realm of tribal art. He loved to visit every museum, and we’d seek new, far away destinations every year to explore.

Jim declared in reflection he had lived a fabulous, enriched, full life with no regrets. He went to work with daily anticipation and excitement, and said not many people could feel that way about a job. He relished all travel, cultures, and art.

Born in Los Angeles, he studied International Relations at Pomona. Jim had interesting, diverse occupations before his gallery opened in 1972. After college, traveling Europe selling Encyclopedia sets to American military; in Rome with his young family living among famous expat writers and artists; arriving in San Francisco with little funds and driving Yellow Cab; as a ceramicist in a studio next to Peter Voulkos; a bookbinder working on Howl, by Allen Ginsberg for Arion Press; school teacher, and leading collector art tours to Africa in late seventies; were a few of his careers. He read avidly, being well versed on all subjects. He dealt in contemporary and tribal art and then focused exclusively on tribal. He kept his first African piece bought in 1954. He had the first tribal gallery worldwide to hold thematic exhibitions. We exhibited in art fairs, and he appraised many fine collections. Jim was proud to serve on the Cultural Property Advisory Committee for the White House for 15 years, among other accomplishments.

We were together over twenty-eight years, and I’d tease I was only his 4th wife. He loved his daughter, three sons, and granddaughter. He had a fascinating family history in depth on both sides. He was a fantastic raconteur of tales and had reflections on all subjects. Jim was a true Renaissance man. He was approachable, and would hit it off with any stranger and they would part having enjoyed their encounter.

In 1981, he was the first survivor of a deadly spinal tumor and rare lymphoma, yet purchased his home despite that crisis. During health challenges, we grew even closer with love for each other. He was a survivor when given four months with metastasized kidney cancer. He rejoiced in the De Young Museum Celebration of His Life, which three dear friends gave for him. Jim felt it was his memorial and how fortunate for him to be present. He lived and traveled 2-1/2 years more.

We had bookings for Paris. We were always full of love and optimism in face of challenges. One can only celebrate a life well lived and follow Jim’s example.

I thank all of you with much Love from Jim and me, Lin

James W. Willis 27 September 1934 – 2 September 2019